Science, echo chambers, and why facts are never enough.

Social media is transforming the way we engage with one another, often striking a delicate balance between bringing ourselves closer together and isolating each other. What social media has shown us is that humans love interacting with other people. We love having others agree with us, and we love jumping on social bandwagons and lashing out at others with opposing opinions just as much, some times.

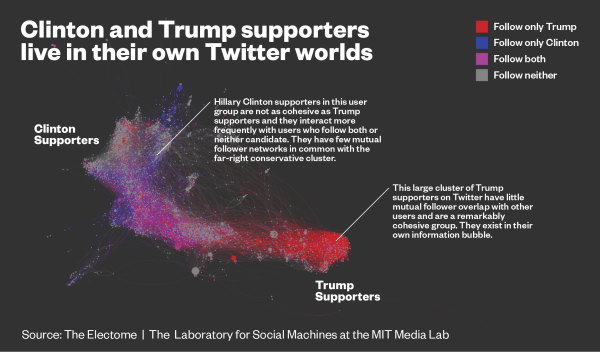

Let’s look at a topical example of social media usage, like US politics. Here, research from MIT has shown that not only do Trump and Clinton supporters live in their own little social bubbles on Twitter, but that the nature of these bubbles is very different too. Trump supporters form a cohesive bubble, whereas Clinton supporters are more broad in their interactions.

What is a social media bubble or ‘echo chamber’?

Wikipedia defines an echo chamber as this:

A metaphorical description of a situation in which information, ideas, or beliefs are amplified or reinforced by communication and repetition inside a defined system.

In reality, this manifests itself in the form of polarised and isolated groups, in which people tend to promote their favorite narratives, while ignoring conflicting ones and resisting information that doesn’t conform to their pre-existing beliefs. This should be of grave concern to those who support science communication as a narrative whereby we simply fling facts at people and then expect them to change their beliefs as a result of this. This is the sort of arrogant elitism that actually puts people off, rather than winning them over.

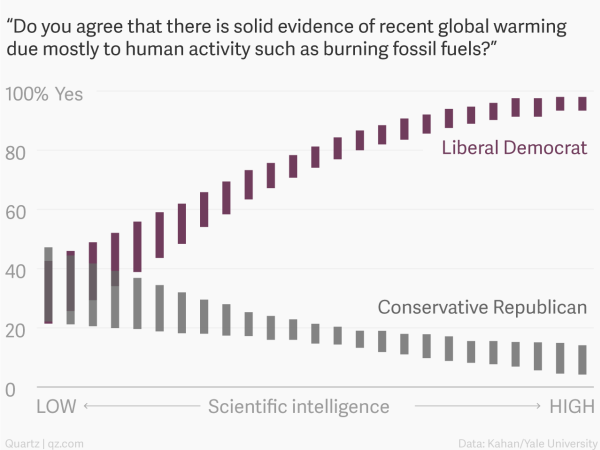

Recent research has even shown that people won’t use science in a ‘rational’ way that we might expect, but rather to justify and reinforce their pre-existing beliefs, and even become more partisan in the process.

But do you know what’s worse than having a personal echo chamber? Remaining silent.

And do you know what’s worse than only listening to like-minded people? Listening to no-one at all.

Features of an echo chamber

The notion that an echo chamber exists as a self-congratulatory, monochromatic, static entity seems to me quite simplistic. It’s a nice way of dismissing someone’s efforts or viewpoint, which makes it quite appealing to wield around in arguments instead of, oh I don’t know, providing useful evidence or commentary.

Anyway, all you really have to do is spend 5 minutes on any social media channel to see the range and diversity of perspectives, experiences, cultures, belief systems, backgrounds, and personalities around, and you will realise that the concept of an ‘echo chamber’ is pretty complicated.

So here are the questions I’m going to be thinking more about in the future, in the context of science communication and academia:

- What is the information composition of an echo chamber?

- How permeable are chamber walls?

- How do we expand or perforate the chamber?

- How do we ‘break’ into someone else’s chamber?

- To what extent do different chambers overlap?

- How does scientific research behave compared to different types of information in these dynamics?

Does ‘open science’ have an echo chamber problem?

I would hypothesise that the problem is perhaps not as bad as it seems, or is sometimes communicated. Or at least, is much more complicated than one might imagine. Small chambers might exist, but do you know what we also call them when we’re not being negative? We call them communities. Where like-minded people come together for support, discussion, or simply to recognise the existence of a commonality. We don’t call it an LGBT ‘echo chamber’ because it’s where the LGBT people go to for support, discussion, or advice – we call it a community. We don’t call it a ‘Christian echo chamber’ because everyone reads from the Bible. We call them communities, or congregations.

So one extra question to answer would be ‘When do we define an echo chamber as a community?’

There’s a lot of research out there on how social platforms like Facebook algorithmically and personally create echo chambers for users. But it gets hurled around quite a bit too, especially by academics. For example, the ‘open access echo chamber’ is often used in a fairly perjorative sense to attack those who support the principles of open. And vice versa, some ‘open advocates’ might use the slur ‘legacy publishers’ in the context of an out-dated echo chamber within the scholarly publishing industry (guilty).

As someone ‘inside’ the ‘open echo chamber’, I don’t see it as that. I genuinely see it as a community, where different voices are amplified and listened to, and where new and conflicting perspectives are discussed and embraced. Anyone who has ever attended an event like OpenCon can testify to this.

To that end, the creation of ‘echo chambers’ actually could be positive in bringing people together. It’s just what we do subsequently that becomes important.

Break down walls, burst bubbles, and build bridges

We create magic in this world when we break down walls and replace them with bridges. That is one major principle driving the ‘open movement’, and emphasised quite a lot at this year’s OpenCon, with the added dimension of the dark political times in the USA.

What we need then is to figure out how to break down chamber walls should they exist, pop bubbles, and find ways of engaging people and groups – especially those who might feel isolated for whatever reason – and do a better job of connecting people in the future.

One way to not go about this as scientists, which is often not only performed by celebrities, but praised and applauded at, is to throw facts at people and expect their entire belief systems to collapse. And then look around in arrogant bewilderment when that doesn’t work. This matters for everything, from showing graphs about climate change and evolution, all the way through to, oh I dunno, the massive increase in prices in subscription fees to publishers.

Scientific engagement should not be a publicity stunt

If you want to break down barriers, if you want to win hearts and minds, then you have to do so on a deeper, and often more personal level. This involves listening often being the first step. It doesn’t matter if you’re an ‘expert’ on something or not; engagement needs context to work with, and you don’t get this by simply blasting out information. A huge problem here is that often scientists will equate ‘science’ with ‘evidence’ or ‘reason’, and therefore expect attitudes to change when presented with research. If you come from a platform of purely science, and refuse to actually do anything to engage on a personal level, don’t be surprised when people resist or begin ‘hating on’ experts and expertise.

This is actually a fairly unpopular opinion among scientists, because it means that science, shockingly, does not hold all the answers and is not always right. It also means that they have to talk to people, and from a platform of equal level, and that’s something that a culture perforated by rife egotism and arrogance isn’t exactly fond of.

Look at science celebrities, like Prof. Brian Cox, who thinks that simply showing a graph to a ‘climate change denier’, a term again which I’m sure they love to be called, will be enough to convince them of the reality of it. What utter elitist, arrogant, and naive bullshit. But in this example, look at how he’s cheered on by the baying crowd. I’m sure the ‘denialist’ went home and had a long, hard look at the science behind climate change as a result. One simple rule of scientific engagement that I shouldn’t even have to write here really is: Don’t be a twat about it.

We’ve had scientific evidence of dramatic climate change now for decades, and still people resist it in various ways, so clearly there is something more to engagement than just ‘science = opinion.’ Go out there and find why people don’t accept it. Expand your bubble, and try and understand theirs. You learn by engaging, not by pompously wielding facts around like some superior overlord of science.

And you know what? No matter what someone’s views on something might be, I guarantee you you’ll have a much more progressive and respectful dialogue with them once you get off that mighty high horse that science has propped you up on. A surprising number of people discuss things rationally when you don’t come across like a pompous asshole.

Recognise that different people think differently to you and have different beliefs. That’s a way of breaking out of an ivory tower, and using your knowledge to make a real and lasting difference for people.

Curiosity taught the cat about climate change

If you want to make a real change, get people curious! Science is exciting enough by itself. Look at the impacts and history of climate change – use it tell personal stories, to construct narratives and meaningful messages, and let the natural curiosity we have as humans do the rest.

Put it into context. Why does someone not accept the scientific evidence? What is their personal reason for not doing so? Don’t make them feel shit for it, that is quite literally the worst possible approach you could take.

Find the angle, make it work. It starts by acknowledging that facts are never enough.

Shockingly, I like the comment here by Lisa to finish off (also partial inspiration for assembling these thoughts here):

The point is that echo chambers are a collective responsibility to avoid, and we should do more to pop them and embrace alternative viewpoints to our own, and engage with them with civility.

“One simple rule of scientific engagement that I shouldn’t even have to write here really is: Don’t be a twat about it.”

Why don’t you practice what you teach?

“What utter elitist, arrogant, and naive bullshit. … not by pompously wielding facts around like some superior overlord of science. … when you don’t come across like a pompous asshole.”

And why do you assume that people have not tried what you teach and noticed it does not work with the extremists on the internet? That people may have concluded that you communicate science to inform the onlookers and not the extremist who is beyond hope.

But it is good advice for talking to real people in real life.

Hi Victor,

Are you calling me a twat for calling out condescending mockery from a ‘celebrity scientist’? That doesn’t make much sense to me.

Engagement of this sort does work better, that’s why we even call it ‘public engagement’ these days. There are whole swathes of literature dedicated to this now.

Jon

Good points here, but I would add one more ‘meta-question’ that often gets overlooked in scicomm: *why* are you communicating? This determines a lot about communication style. To take the Brian Cox example, you are of course right that Roberts was highly unlikely to have an overnight Damascene conversion. However, the episode ticked all the right boxes in terms of speaking to group identity (i.e. generated large amounts clicks on Guardian, Buzzfeed etc). So it was a v effective communication device in that way, and some people think this is worthwhile – there is a performative function in humbling (or attempting to) non-believers. It is almost as if people such as Roberts *have* to exist as a means of bolstering group identity.

Of course, one may not think scicomm should perform this function, but this would be seem to be the rationale for stunts such as Cox’s.

Hey Warren,

Thanks for commenting. Sure, I agree on the why. And this ties it into the echo chamber thing again – it seemed to me just like pandering to the crowd, but by being pretty condescending. That doesn’t create cohesion, it causes divides. While I can see the possible purpose, I don’t see the point in it.

Jon

Many viral posts these days pander to the crowd, and affirms a belief that their specific group is of special intelligence and insight. Furthermore, I’d bet that an analysis of viral posts these days would likely find a strong element of condescension for the other side. That said, do you think it would be possible to have a platform that reduces echo chambers? I’ve written about it on medium: https://medium.com/@the7th.us/make-it-stop-the-echo-is-killing-us-d7d35dff01dd#.g5fch5eu9

Any thoughts or feedback?

I appreciate your effort as a supposed “climate-denier”. Very kind of you thinking I will come to “reason” if I am kindly treated. This makes me just stupid, or childish, and not necessarily evil. I guess this is an improvement. Really.

Problem:

Let me tell you a secret. I am not resisting anything. I am just looking. And I would be very glad if you show me all this evidence of dramatic climate change. You don’t even need to be kind; I am not a child since a long time ago.

We may have a problem with the meaning of evidence, though. For some folks, something a scientist thinks is going to happen is not evidence of climate change, but just evidence of his not necesarily substantiated opinion.

To make it short. Thanks, but no. I am very happy with the graphs. For instance, “dramatic climate change”:

https://plazamoyua.files.wordpress.com/2013/10/cet-trend-profile.png

Hey,

Thanks for commenting. I didn’t mean to imply that ‘climate deniers’ are childish or anything! Just that different people treat different types of evidence in different ways and that’s something we need to account for. The ‘treating kind’ thing is just something I kinda hold to all human endeavours.

Jon

Personally, I’m rarely trying to break down barriers. Instead, I’m usually trying to impel meaningful action among the 2/3 of the population that believe climate change is a problem. I use data and graphics, I don’t do it pompously, and if it gets through to the skeptical, wonderful. But fighting a decade of minsinformation, disinformation, and politicization is generally a low-percentage path, in my experience.

I agree with and applaud your emphasis on listening as the first step to effective communication. As someone active for five years in the debate about public policy implications of climate change, here’s a test to determine if you have listened: repeating back what you are told. It’s part of basic training for social workers. If you cannot accurately re-state what you have been told, you have not been listening.

Failure to do so is commonplace among scientists discussing climate change. For example, objections to anthropogenic climate change being the dominate form of climate change since WWII become “denying climate change.” Challenging claims about the probability of extreme warming during the 21st century becomes “denying climate change”.

Rebuttals to strawmen arguments have become so common as to make the policy debate a cacophony.

I suggest a follow-up post listing common failures to communicate of scientists and skeptics. It would help to move from somewhat abstract terms such as “listening” and “communicating” to specific problems and methods to overcome them.

Hey Larry,

Thanks for taking the time to comment here.

I think you’re on to something there. Labeling people as ‘climate change deniers’ in a pejorative sense is unlikely to win many friends either. I’ll look into your suggestion for a follow-up post too, but it’ll take a lot of research and time! Bear with me 🙂

Jon

Jon,

“Labeling people as ‘climate change deniers’ in a pejorative sense is unlikely to win many friends”

I agree, but that’s not the point I made in my comment above.

Rather, it’s that many people advocating public policy action to fight anthropogenic climate change prefer responding to strawman, rather than listen to and address skeptics’ objections. Use of insults — such as “denier” (with its association with holocaust denier) — is just one example of this method to avoid debate of skeptic’s beliefs.

Another example: when skeptics disagree with policy advocate’s description of AR5’s worst-case scenario (RCP8.5) for *future* warming as “business as usual”, some scientists reply by citing the consensus about *past* warming (“It is extremely likely that human activities caused more than half of the observed increase in global mean surface temperature from 1951 to 2010”). This suggests, to be charitable, that they’re not listening.

I can give many more examples.

Your advice to scientists about listening is essential. That they repeat back what they heard — accurately and fairly — not only demonstrates listening but also provides a firm ground for their replies. It’s a necessary step to re-starting a productive debate about public policy action. I suspect it is not a sufficient step.

Discussing what additional steps are necessary to re-start the debate would make another good column.

Hi Larry

” it’s that many people advocating public policy action to fight anthropogenic climate change prefer responding to strawman, rather than listen to and address skeptics’ objections.”

Here is my experience in Listening to and addressing skeptics.

For about 5 years (2007 -2012) I listened to skeptic issues with temperature series. I wrote code ( free of charge ) so they could do their own investigations. I looked at every one of their objections in detail. In 2012

if joined a non profit to do the same thing I had been doing as a hobby. Answering the skeptical issues with the temperature series. We published papers, memos, data, code.. And we addressed every issue they raised. We even used methods they suggested. Our top statistician spent time reading everything top

skeptic statisticians had written and we used the best ideas that skeptics had.

What has been the result?

from my perspective the insults have gotten worse. the claims of fraud have increased.

basically the opposite of what you’d expect.

I’m very happy to accept the ‘scientifc evidence’. Liek observations and measurements

But its a huge stretch from there to

‘I’ve got a computer model that says the End of The World is nigh, so repent Ye Evil Sinners’

which so often is the response from ‘climate scientists’.

You guys have had 30 years to make your point. Mother Nature hasn’t cooperated. And turning up the volume of insults to WarpFactor 11 isn’t going to help your cause one jot.

I wrote a post, as you presumably noticed. It was written in a bit of haste, so feel free to correct anything I may have misunderstood.

I’ll make a couple of additional comments. One issue with your post is – IMO – quite nicely illustrated by Larry Kummer’s comments. Larry writes a blog that – in my view – one might describe as “more misinformation than not” (at least when it comes to climate science). Not as bad as many, but not great. A regulat theme (as he discusses above) is what it would take to restart the debate. As you may note, the fault lies with everyone else (advocates of climate policy, scientists, etc). Your post has essentially bought into this narrative; the problem are those dastardly scientists in their echo chambers, who don’t listen and call people names (I exaggarate a little). It ignores the host of misinformation out there. That may not have been your intent, but it’s going to be how it will be interpreted by those who want to find another reason to bash scientists.

Having said that, what you suggest is not a bad idea. It’s pretty much what I would have thought 4 or 5 years ago. My view now is simply that this is an incredibly difficult topic in which to engage publicly and that there isn’t an obvious ideal/best strategy. I suspect, in fact, that many have actually tried what you suggest and have simply come away going WTF! There’s probably a limit to how many insults (personal and towards scientists in general) that most people can take. Of course, if this is the strategy that you think works best for you (and that you’d like to promote) go ahead; I think we should try everything. I just don’t think this somehow justifies calling those who choose to engage differently “twats”. YMMV, of course.

Hey there,

Yeah, I saw your post, thanks for keeping things rolling! I don’t pretend to the arbiter of all truths, and am always happy to be shown wrong or even just to generate more discussion on these topics.

I’m not laying the blame on anyone. I’m just saying maybe there are better ways than the condescending/elitist/ivory tower (etc.) approach. I do think scientists have a lot of problems with egotism though that certainly interfere with these sorts of issues.

Fully agree that this is difficult. I’m glad my area of expertise is dinosaurs, much easier! But I still stand by acting in a condescending mocking tone to be twatish. I’d have been the same 5-6 years ago, but then get into policy and science communication and it was a bit of a mind-blowing experience about how to actually interact with people. But yeah, also agree that there is no one single approach. Being flexible and adaptive works best, but still there is a manner in which you can conduct these things.

Jon

Thanks for the reply. One problem I have with referring to others who engage in this topic as “twats” is that it’s the kind of thing I expect on what I shall politely call “skeptic” blogs. Being insulted on “skeptic” blogs is expected. Being insulted on other blogs, not so much. There’s also an element of irony to you choosing to do it. Your post is presumably aimed at science communicators. Your message is “don’t be a twat” when trying to engage publicly with others. So, you’ve essentially decided to call those with whom you’re trying to engage “twats”. Hmmmmm? What’s that saying about practicing what you preach?

The other problem relates to the issue of facts not being enough. I largely agree, with the caveat that we should not underestimate the role that providing these facts plays in countering misinformation. However, I probably agree that if some would like to actually play a role in changing public perception, then facts are not going to be enough. Whether you like it or not, one possible alternative is to make it appear silly to hold certain views. It might not be a strategy that you would choose to emply. It might not even be a strategy that I would choose to emply. However, it’t not obviously a strategy that won’t be effective. It might even seem “twatish”, but if your message is that facts aren’t enough, then maybe you have to accept that some will adopt strategies that may not seem ideal, but that may be effective.

I’m not a skeptic blogger. Look at the name of the url for this page. 😉 I’m also British and this is fairly commonplace language.

The post isn’t really aimed at anyone either. It’s just a collective of thoughts I had, that might be of interest to some who work in Sci Comm. And I’m not calling anyone a twat, just saying “Don’t be a twat.” I mean, it’s not difficult.

Yes, I know. I didn’t say you were. In a sense that was my point; I expect scientist who publicly discuss climate science to be called twats on “skeptic” blogs, not on blogs that I wouldn’t describe in that way. I’ve been proven wrong.

Technically I’m British too, and it’s not language I use all that often. Each to their own, of course.

It’s hard not to interpret you as calling Brian Cox one, and you seem to think that there are some style that are worthy of being described as “twatish:, but okay.

Anyway, I suspect that this discussion isn’t going to progress any further, so I’ll leave it at that.

At a political/public level – name calling ‘usually’ works – an example – accusations of “racist” & “bigot” was used for years to stifle people on the immigration debate, whilst it is still used to shut down opponents, – Gordon Browns encounter with a Labour voter (and a Sky news microphone) punctured that label a bit.. and if everybody is quite literally Hitler (think Romney several years ago) what do you say when another actual Hitler comes along in say Eastern Europe at some point?

calling people “climate deniers”- was/and is just a lazy way to attempt shut down opponents in a political/policy debate. There is some irony that this was observed by John Cook, just prior to starting Skeptical Science.

“I’ve been following the global warming argument closely of late and I’ve noticed both sides often fulfill Godwin’s Law. Global warming advocates liken skeptics to Holocaust deniers (akin to a Nazi). Skeptics compare Al Gore’s public awareness campaign to Nazi-like propoganda. It’s lazy debating – why discuss the issues with facts and logic when you can easily write off your opponent with a derogatory label?”

– John Cook – 2007

http://web.archive.org/web/20070905124940/http://www.cricket-blog.com/archives/2007/05/13/JCs-Law/

http://www.cricket-blog.com/archives/2007/05/13/JCs-Law/

Recently Naomi Oreske’s was accusing scientists like James Hansen of some sort of denial.!

There is a new form of climate denialism to look out for – so don’t celebrate yet

Naomi Oreskes

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/dec/16/new-form-climate-denialism-dont-celebrate-yet-cop-21

so calling people ‘climate deniers” in 2017 I think now informs the public more about the name caller, than those called names.. and doesn’t really work anymore..

Interesting article, but I think there is a basic underestimation of the power of echo chambers. In my humble opinion they aren’t communities, but more like tribes, and tribes stick together. You might be able to convince a *person* that climate change due to human activity exists, but convincing a tribe that has made denial a tenet of their identity is going to be much, much more difficult. Climate change has become such a political point of contention that in many cases denial has become an article of faith, a part of their identity. In a climate of anti-intellectualism, climate change is seen as an agenda that the educated left have used to victimize these groups. With all of these factors going against you, no matter how open, how much one listens, and with how little twatosity one approaches the subject, you are unlikely to find anyone willing to really listen, or at least that has been my experience.

I think that there are a lot of definitional problems here that are being taken for granted.

First, what does “science communication” even mean? That you used one of Kahan’s graphs indicates that you are familiar with his work – in which case then you must know that he talks often of how in most cases where people are evaluating communication about topics related to science, the communication is more or less non-problematic. If he’s right about that, then why are we focusing on such a limited context – that of communication about climate change, or other polarized contexts – to extrapolate lessons to be learned about “science communication?”

Indeed, I think it may be more useful to look at communication about climate change or other polarized contexts not as a manifestation of “science communication,” but as a manifestation of communication between people who are deeply polarized, and therefore more likely to follow the pattern whereby the more communication that takes place, the more there is a reinforcement of the polarization (a pattern that doesn’t exist with most communication on scientific topics).

And then the definition of “echo chamber” is also problematic. The existence of an “echo chamber” is, IMO, probably more an artifact of the orientation that a given individual brings to a communication act and communicative environment than it is anything in particular about whether there a largely shared orientation among the participants in a given communicative environment. As such, the reactions to a communicative act is certainly not exclusively, but I’m not sure even predominantly, a function of the “speaker” as it is the “listener” in the communicative context. But regardless of what predominates, it certainly makes little sense to focus exclusively on the speaker w/o due consideration of the listener.

As a useful example, consider Larry’s “listening” here, where ironically he largely skips over the role of the listener as he talks about the importance of listening:

==> Use of insults — such as “denier” (with its association with holocaust denier) — is just one example of this method to avoid debate of skeptic’s beliefs. ==>

Now on the one hand, I think that there is a lot to question about the communicative intent of someone who is using the term “denier.” What, really, is the goal of such as “science communication?” In order to judge it’s effectiveness, you have to assess what the goal is. But on the other hand, what is the goal of a listener if they hear the term “denier” and make an association to holocaust denial? With such a question, can see that it certainly isn’t only the “speaker” who determines the “effectiveness” of “science communication.”

Another example that Larry has provided is here:

==> I agree with and applaud your emphasis on listening as the first step to effective communication. As someone active for five years in the debate about public policy implications of climate change, here’s a test to determine if you have listened: repeating back what you are told. It’s part of basic training for social workers. If you cannot accurately re-state what you have been told, you have not been listening.

Failure to do so is commonplace among scientists discussing climate change.==>

And then there’s the question of how do we measure “effectiveness?” Do we measure it by examining a change over time in people’s views? Do we measure it as people becoming more knowledgeable about a topic? Do we measure it by someone’s increased uncertainty (along the lines of “the more you know about something the more you know what you don’t know)? This measurement task is extremely difficult, in only (in the least) because people are likely to hide a greater uncertainty (making them feel threatened or insecure) by doubling down on a greater amount of expressed certainty.

So in describing his listening experiences, Larry notes certainly behaviors only among “scientists,” and further goes on to describe those behaviors as “commonplace.” I would suggest, at least as revealed in his description of his listening experiences, Larry has been very selective. When listening reflects that kind of selectivity, it says a lot about how to evaluate the effectiveness of a communicative interaction. What is the goal of the listener if their focus is so selective?

I think that in order for an assessment of the effectiveness of science communication to be meaningful, rather than just an exploitation of a vague concept in order to advance a rhetorical agenda, there needs to be some clear definitions. For example, what is the communicative context that you’re speaking about? Is it one of deliberative democratic processes where communities are attempting to reach consensus on policies that incorporate scientific information? It is an online discussion forum, where people are very focus on affirming identity-orientation through a display of identity-protective cognition (if you’ve read Kahan’s work, then you should know what that term refers to)? Looking across those different contexts, I think that we’d come to many different conclusions about the “effectiveness” of science communication.

What is the goal of the listeners? Is it to be informed in areas where they lack knowledge? Is it to reaffirm their preexisting beliefs? Is it to reinforce their identity-orientation, largely by raising their own sense of self by lowering their view of an “other?

“Put it into context. Why does someone not accept the scientific evidence? What is their personal reason for not doing so? Don’t make them feel shit for it, that is quite literally the worst possible approach you could take.”

Well intentioned though this is, this in itself is unhelpful. The implication is that “the” evidence is binary in nature, and not accepting “it” has to be personal and somehow political or value driven.

A better approach may be to ask “What evidence do you find compelling?” and “Why do you assign weight to that particular line of evidence and not to another”

Hi Sean,

Sure, that is one implication – the way in which we perceive things is entirely different based on a multitude of factors. That’s the whole point I was trying to make about putting science in context.

If you start by asking people about the evidence, it assumes they know about the science intrinsically and are just rejecting it for one reason or another. I prefer not to make those assumptions straight off!

Jon

Jon, Here is what ATTP said at his blog:

The problem for ATTP and why your advice perhaps challenged him is that his track record is that he simply doesn’t show any respect for those who he disagrees with even on subjects where ATTP’s knowledge is pretty lacking. He also like a lot of climate blogs runs pretty much an echo chamber. I found his comments about Larry Kummer above a little disingenuous because ATTP has banned a significant number of people whose views he doesn’t like but who are normally polite and relevant. Kummer is not a “misinformer” but simply another voice in the debate. There is a good summary of these issues with ATTP is at

https://ipccreport.wordpress.com/2014/08/16/and-then-theres-hypocrisy/

In any case, one sure way to spot an echo chamber blog is by the presence of anonymous and rude commenters who try to discredit anyone who strays from the doctrine the site promotes. You will see this at Ken’s blog for example.

Ken also said in his post: “Undermining those who are mostly right about the science because you disagree with their stratgey is, in my opinion, exceedingly unhelpful.” I think, Jon, this may have been aimed at you or perhaps Ken is just feeling a little guilty and your post hit the bullseye.

In some sense, David Young’s comment illustrates what I am trying to get at – if you get out of the bubble and publicly discuss a contentious topic, you will have to get used to various people insulting you for doing so. What Jon suggests is the ideal, but expecting people to achieve it in the face of all that will be thrown at them is a good deal harder than it may at first seem. In my view, if people want to comment on how science communication should be done, I think they should consider all sides of the exchanges that will take place, not just one.

The only other thing I will say about David Young’s comment is that his claims about me and how I run my blog are simply not true. To be clear, I don’t claim that how I’ve engaged is some example of how it should be done, or that how I’ve run my blog is how a blog should be run. However, I don’t think someone should be too quick to criticise blog moderation until they’ve tried to moderate a blog that regularly got many hundreds of comments on a single post. I don’t get that many these days, but there was a period when it was pretty active. It’s not easy if you’re trying to maintain a site where discussions remain reasonably civil. Sometimes you just end up banning some who seem incapable of following the comment policy.

As for the quote of mine that David Young includes in his comment, it is – unfortunately – my experience. I don’t think this is a good thing, and am not pleased about it, but it is what it is. As far as I’m concerned, anyone who thinks that simply being respectful, polite, and patient will make such exchanges worthwhile and constructive, is being naive. I’d be happy to be proven wrong, but I’d be very surprised if it were the case.

Jon, I would not take Ken’s comments about your post very seriously as I explain below and list the reasons. Summarizing, he is an outlier in a dialogue where there are many, many respectful individuals and exchanges between those who strongly disagree. I know first hand because I’ve had those respectful exchanges many times myself.

The problem here is that Ken’s blog and Ken himself have alienated a number of honest scientists and in some cases prominent scientists. The list includes Paul Matthews, Richard Tol, and Judith Curry all of whom have been attacked in pretty one sided ways at Ken’s blog. Roger Pielke Sr. was also in that category until things were patched up with a joint post. Roger Pielke Jr. has come in for harsh treatment too. Ken has treated me rather disrespectfully too.

1. That kind of thing will naturally tend to have the result that constructive exchanges become more difficult. So of course Ken’s negative experience is partially a result of his own behavior.

2. Thus, Ken’s experience really doesn’t say much that is unbiased about science communication except perhaps as an example of how the logical consequence of disrespect for those who disagree will lead to failure.

3. To understand the climate blogosphere you must realize that there are a number of very viscous blogs attempting to “enforce” the so-called consensus by intimidation. Ken in the past has been in this group as is Skeptical Science, and Hot Whopper (an example of internet hatred and contempt if there ever was one). There are also a number of contrarian sites that have a lot of posts that are of low quality. To Ken’s credit, he has been trying to turn over a new leaf, but the embers of his earlier style remain warm.

4. There are many very constructive exchanges on climate between people who strongly disagree but who respect each other. Myself and Nick Stokes have had numerous educational exchanges. Ed Hawkins similarly seems to do a good job at his blog. I have had very constructive exchanges with Michael Tobis. Richard Betts of the MET office is another example of someone who inspires a constructive attitude in virtually everyone. Nic Lewis despite being a newcomer to climate science seems to inspire respect in virtually everyone.

5. Perhaps the majority of comments at Ken’s blog are from anonymous and obviously non scientist persons who have a track record of disrespect and insult. That’s a prime indicator of an echo chamber. Richard Tol and myself who used to comment there frequently have experienced their attacks frequently. If you are interesting in verifying it you can easily do so by looking at posts at Ken’s blog about Richard. I also featured prominently on one comment thread there and suffered just as badly.

6. Ken has banned a significant number of individuals who were generally polite and on topic. I won’t give the list here due to length of this comment.

Thus, Ken’s experience is an outlier and really just a consequence of his peculiarly confrontational and disrespectful style and says nothing about whether your post here, Jon, is important or right. I personally think your post makes some very important points.

Okay, this comment thread appears to be becoming about me, rather than the topic, which was certainly not my intention, but might somewhat illustrate my point. I’ll make one final comment (or, try to make it final 🙂 ). It’s fairly easy to make suggestions about how scientists should engage publicly, and Jon’s are quite reasonable. All I’m pointing out is that what’s being suggested may – in some cases – be easier in theory, than in practice. If a scientist chooses to engage publicly about a contentious topic, there is a high chance that some will choose to target them personally, rather than engaging with the topic under discussion. It’s hard to know how one will respond to that until it has actually happened. It might also take people some time to work out what works best for them.

Given this, it’s certainly my view that if someone thinks they understand SciComm and thinks they can contribute to how it’s undertaken, they should sometimes be careful of how they characterise how others engage. It’s quite possible that they may not really understand what that person has experienced and why it is that they’ve chosen to engage in that way. If public engagement is to be a dialogue (rather than simply a monologue by scientists) then I don’t think the responsibility for the tone of that dialogue should rest entirely with one of the groups involved.

Derailment for the win.. Yes, it certainly wasn’t my intention to wake the hornets nest on this one. The message I wanted to convey was simple: Sci Comm of any sort is DIFFICULT! But it can be a lot easier when it’s not done arrogantly, in a mocking or condescending way, and when one goes further than just throwing scientific facts around like gospel.

I’d love to see more about the generation of the data, how calculations were done etc. for the climate change example. That would be sweet, and actually engender more trust in the science if it’s visible and transparent as a process, not just a final result. But yeah, I agree that it’s difficult, and that there’s no magic bullet method for it.

Also, I don’t really care about past experiences – that doesn’t excuse someone with an enormous status and position of power in the research community to behave as he did. Like I said, this creates more divides than anything else, and I don’t see any point in it. Yes, you can sympathise with the frustration, but rise above it. That’s how we should be as scientists and as humans.

“I’d love to see more about the generation of the data, how calculations were done etc. for the climate change example. ”

You know I spent 10 years begging for that and then actually doing it.

Guess what?

1. People still refuse to look at the data.

2. They still refuse to look at the code

3. If you write in a language they dont like, they will attack the code, not the science.

4. If you supply your code in SVN, they will demand Git

5. If your website of data isnt organized or updated to their liking, they will call you a fraud

6. If you post all your relevant data, they will ask for even more, and criticize you for not being

as fast as they think you should be.

7. If you prepare special datasets for them ( cause they dont know what they are doing ) They will

never publish or acknowledge your work.. basically they give you homework, and if you dont

answer their questions in a timely fashion.. they accuse you of lying, being a fraud, stonewalling.

So ya, back in 2007 ( go check) I spent a bunch of time demanding that climate scientists share their data and code. All that history played out in climategate ( yes, I’m that steven Mosher) On the other side of climategate

There has been a change.. More data is available and code as well. I literally donated years of work to make the data and code more open. The naive belief was that once people could see and use the data and tools themselves that at least one small corner of the fight would get civilized and folks could reach agreement.

Boy was I wrong. The Opposite happened.

@protohedgedog I find your article interesting and relevant — there is a dearth of analysis regarding the nature, characteristic, even existence of “echo chambers” and how to deal with it.

I think however, that your using of the “climate change topic” to illustrate your ideas is very ill informed. A lot of domain experts have tried and are trying to communicate these thing efficiently since decades. With quite a lot of consideration of results in science communication. And with a lot of success in any area that actually can be touched with “science communication”. That is involving an audience that is receptive to rational and scientific argument on any, even the most simple level.

When talking to a certain audience all this fails. One can argue that it would be better to stop talking then. A lot of people think it would be unwise to leave the public stage to the fossil fuel interests though. Consider Victor’s remark that the audience might actually be the onlooker.

Give your background: Do you have a track record convincing Young Earth Creationists that evolution is a thing? If yes, by all means lecture those condescending wanna-be climate science communicators. If not, your argument might profit from some humility.

If you’re focusing on the example of climate change, you’re kinda missing the point. I don’t care what the topic is about, all I’m saying is when engaging, don’t be a dick. It’s not too difficult a message to follow, an frankly I don’t really understand why this is escalating into such a big thing. Clearly I wandered into the climate change version of a soap opera by mistake.

And yes, I have regarding YEC. Like my parents, for example. Often it’s very odd – they will accept ALL the evidence behind evolution (e.g., adaptation, descent with modification), but reject the concept of evolution itself, because the term is stigmatised. Like you can’t believe in evolution because x, y, z. Which is one of the reasons why it’s so important to consider more than just science and develop the context and understanding behind it.

And yeah, people get pissed when you talk to them some times about these things. It’s emotional, I understand that. But that doesn’t mean you should sink down to that level, just as with any other sort of conversation you have with anyone, ever. And I think you kinda nail it – people have been trying for decades, and what have we seen as a result? Slow movement, still a generally poor understanding from some very important people about CC. So something ain’t right, and maybe it’s because a lot of scientists don’t understand that you have to go beyond the science some times to make things work. This isn’t about ‘post-facts’ or anything like that – it’s about putting science in a broader context.

“People have been trying for decades, and what have we seen as a result? Slow movement, still a generally poor understanding from some very important people about CC.”

I don’t agree. Everybody who cares about being knowledgeable about this topic is, by know. The educational resources, including experts answering in blogs, are outstanding. “Poor undestanding” ranges from commercial/political interest astroturfing to refusal or inability to understand because of religious beliefs / peer group pressure or other social factors that can’t be overcome by rational argument.

I think “science communication” isn’t really the problem. It is the “go beyond the science” – part where nobody really knows how that is supposed to look like. At least not scientists, in general. There are notable examples, e.g. Katharine Hayhoe, who seems to be able to get through to an otherwise difficult audience by presenting “Global Warming Facts for Faith-Based Decisions”.

“it’s about putting science in a broader context”. Not sure what you mean by that. My perception of the broader context of climate science is that science communication doesn’t matter anymore. It is a political fight in which claims to scientific authority are invoked as rhetorical device. On that turf it might well be the better option, in some situations, to appear as a dick to some.

Right, you just made my point. There is more to it than just ‘educating’ people with science – there are political or commercial, or cultural and social, aspects to consider. And that’s the context that science needs to be put in.

hwv, You seem frustrated by the fact that a lot of people don’t care that much about climate change and thus don’t really care what experts say about it. That is a fact of life and of the way human beings think and behave. There are many many challenges faced by human civilization currently and in the past. Trying to prioritize those challenges is a question to a large extent of values. Science can only provide facts and can say nothing about people’s values and priorities. And an additional effect here is that the public has grown weary of all the “crisis” reporting and propaganda from advocacy organizations. Some of it has even emanated from “scientific consensus” and the government, for example on the issue of dietary fat.

It is a favored modern virtue signaling technique to become a public advocate for some cause you really really believe in. Fear mongering often accompanies this virtue signaling and can seem to be required to get people to pay attention to how virtuous you are. And hypocrisy of course merely further alienates the public.

But for those considering the virtue signaling profession, being respectful and polite is the best option. Failure is guaranteed when you are a dick about its, as our gracious host says.

Glad we agree. And apparently natural scientist are in general not very good at doing that. I myself eagerly wait for the climate-sociologists, who keep complaining about having too little influence in climate politics, to take up the torch.

Jon, The main point of your post which you restated as

is quite correct and something most would not disagree with. It is a message that Ken Rice however seemed to disagree with from his blog post response, which I found a little odd. It’s a little hard to tell from his comments here though so it was worth clarification.

My point is merely that its not surprising in the climate debate to see “mocking and condescending” as its a very highly politicized field with many scientists holding strong activist positions and using their status as scientists to try to shut down or discredit honest disagreement. There is more than enough blame to go around here, but climate scientists are far from blameless themselves. The community would do well to emulate Richard Betts or Ed Hawkins or even Judith Curry. There are a lot of activists, like Ken, who have blogs that contribute to the “mocking and condescension” and need to rethink their approach.

You no doubt didn’t know that a relatively straightforward post on science communication would cause such a reaction but it has unfortunately become commonplace in the climate field and among outsider activists.

Thanks for the post, Jon. It’s a good contribution.

The debate exists because the science is ambiguous. Climate change is a grand environmental impact assessment and EIAs are always iffy. Thus reasonable people can look at the evidence and come to opposite conclusions. This is very simple.

Hello David,

It’s nice to have your expert opinions here again, after those which you elucidated for us on our F1000 Research paper. Your comment, “The debate exists because the science is ambiguous.” is rather grand, as we might expect. Do you perhaps have any evidence to support this? It is, irrespective of this, at odds with your follow-on statement, “Thus reasonable people can look at the evidence and come to opposite conclusions.” – this has nothing to do with potentially conflicting evidence, but more bout how people choose to read evidence in different contexts.

Jon

The ambiguity allows different people to take different positions. The weight of evidence in complex cases is relative to the observer, because it depends on what one believes. Even the Baysians agree to this.

If you want an example, the surface statistical models like HadCRU show sharp warming 1978-1997. This is the primary basis for AGW. But the UAH satellite measures show no such warming. Thus some people believe that the warming exists while others do not.

*Bayesians.

If you want to do any sort of effective communication on this matter, using different acronyms isn’t going to help, and nor is cherry picking examples.

I want concrete evidence that there is large-scale ambiguity regarding the status of anthropogenic-induced dramatic global climatic disruption. What you provide, if this is true, is that there was a short warming phase within an otherwise longer phase of cooling based on one source of data, that a single different data source contradicts. Is that correct? What does the overwhelming majority of evidence say? That is the important thing, and what we should base our scientific evaluations on. The important next step is how do we communicate that consensus in an effective way to a range of audiences.

“What does the overwhelming majority of evidence say?”

Unfortunately, there is no “overwhelming majority of evidence”. That is part of the problem. Of course people commonly take sides and argue that one line of evidence is more persuasive than another. Non-scientists might be surprised at how often subjective reasons eventually sway a scientist one way or the other.

Sometimes both sides can be right for reasons that become apparent later, or both data sets fall within the same envelope of relatively large uncertainty that accompanies what are really quite small changes. These types of disagreements certainly occur with other, less politicized, scientific questions. They can rumble on for many decades until a ‘rock-crushing’ piece of evidence appears, as it once did with continental-drift away from mid oceanic ridges before magnetic-anomaly measurements produce symmetrical ‘bar-codes’ either side of the oceanic ridges.

And sometimes the question itself may be ‘incorrect’. In this instance it can be, and is, argued that the surface thermometers are not actually measuring the same thing as the satellites, which measure temperatures up in the atmosphere (where, importantly, increased greenhouse gases should be expected to show their effect most noticeably). Radiosonde (balloon) measurements tend to agree with satellites, but the matter still appears unresolved.

Back on the main topic of the post, there is an interesting corollary/question to the striking figure shown from Kahan’s article: Are people in the right hand side of the graphic likely to change their voting habits as a result of this politicization of a scientific issue? From a personal perspective I can give a very definite “yes”.