Open Access should never be the end game.

Open Access needs to be used more effectively to tear down barriers to research accessibility.

The ‘open’ versus ‘closed’ access debate probably doesn’t make that much sense to many people. Including myself, actually. It’s not immediately clear what either term means in different contexts (e.g., data, review, research, science), or what we actually even mean by ‘access’. And that’s after I’ve been engaged with this whole ‘Open Movement’ for like, 6 years now.

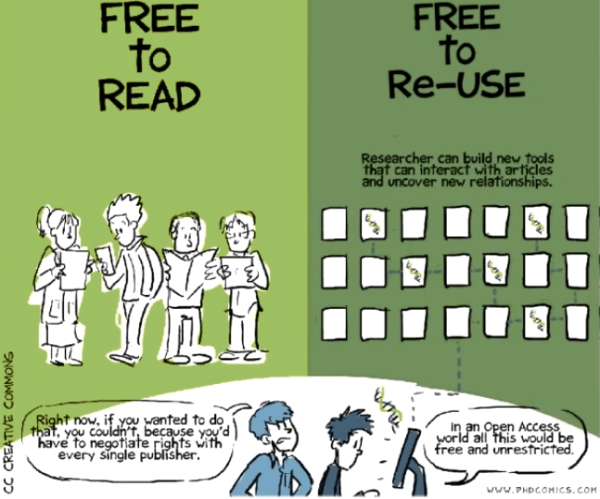

I know what ‘Open Access’ means very bluntly, in terms of anyone being able to read and re-use research articles, but reckon this doesn’t get the importance of it across enough.

For myself and many others, the importance of Open Science/Research/Knowledge/Access, you name it, has always been at least partially grounded in ethics. I believe that every person should have the ability to access knowledge as the output of research or for educational purposes, should they desire. Business models, rampant profiteering, gold versus green, and all that jazz have always been secondary as the ‘how’ of Open Access as opposed to the more important question of ‘why’.

So I don’t feel this simple basis for Open Access is enough, or communicated as effectively as it could be. And often it ignores the much larger issue of accessibility. That’s the ‘why’ part.

Open Access is not enough

I also believe that knowledge must be made as accessible as possible. And by that, I mean transcending or overcoming potential issues to do with language, technical infrastructure, software, disabilities, and anything else which prevents research from being accessible. These are barriers to digestion, understanding, and re-use.

As such, it might be easy to see why Open Access doesn’t really matter to many people – why should they care whether they have access to research papers or not, if they don’t have the technical skills or prior knowledge of a subject, for example, to actually be able to digest the information contained within research articles. Many researchers don’t care about Open Access either, as they don’t see the issue. They have access, so what’s the problem? They can read papers because they are trained to do so, so what is the problem?

My mum just stared blankly at the screen for 10 minutes when I showed her my last paper before I let her off the hook and had to go and make a recovery cup of tea.

Well, I don’t think there is really much of a point in having total Open Access if no one can actually access the knowledge and then maximise the re-usability of it. Knowledge isn’t really that useful if it just sits around doing nothing. If no-one can actually re-use it, beyond simple licensing restrictions.

And that’s just in terms of general understanding and prior knowledge. What if you were vision impaired? What if you were in a rural environment with no internet connection*? What if you can’t afford a computer, laptop, or phone to read papers on? What if you couldn’t understand English, like the vast majority of people on this planet, yet for some reason it is the main language science is performed and communicated in.

None of these things are solved by simply having access to papers. They are made easier, as it means we can take research and re-use it without restrictions to help overcome these barriers to accessibility. A paywall is just one impediment to accessibility.

So for me, I don’t think Open Access is enough, as it only breaks down one barrier. It never was enough, or intended to be so. Open access is a foundation, or a mechanism.

What is Open Access a mechanism for?

But then what is Open all about? Well, for equity in accessibility. For a fair chance at being able to learn. This is why ‘Open’ is important, and why I don’t think calling it ‘Open Access’, or thinking of this as the end point, really works on some levels.

It’s a bit deeper, and more complicated, for me. I see it more being about ‘privileged’ versus ‘equal’ access, which recognises the inequalities beset in our knowledge communication and accessibility systems.

This sort of realisation probably only ever rarely comes to scientists, because they think that Open Access or accessibility isn’t an issue because someone somewhere has spent a fortune paying so they can read research papers (thank, librarians), and have spent years of their lives training to be an expert in a field so they can actually understand and use research. It’s difficult to realise you have this sort of privilege until it is taken away from you. This was one of the things that frustrated me most actually while working at Imperial College (very wealthy) as a grad student (very poor), and trying to convey to staff/students that access to literature was a problem that went beyond just them. I will never be surprised by the selfishness of some researchers.

But anyway, if we want a greater public understanding of science, a more knowledge-equipped society, more informed debates about climate change, evolution, natural resource consumption, mental health issues, drugs, about anything at all, then we have to go beyond just making research papers free to read. We have to recognise all the potential barriers in accessibility, and work harder to overcome them. Initial access is just the beginning of this.

Open Access is fundamental to science communication

We have to innovate more in how research is presented, communicated, and engaged with. Thankfully, there are already whole cohorts of amazing people working in the fuzzy world of science communication and public engagement with science. Just with the rise of things like ‘alternative facts’ (aka bullshit), I think it is clear that we have to do better at making science more accessible to everyone, and do a much better job of putting it in a wider societal or cultural context for different publics.

This ties in with what I said in a previous post about presenting scientific facts to people and expecting miracles to be not only pretty arrogant, but also fairly shallow in our understanding of how people process different types of information. There is more to it than just ‘educating’ people with science facts – there are political or commercial, or cultural and social, aspects to consider. And that’s the context that science needs to be put in.

Science needs to be open for it to flourish, but to really blossom it has to be made more accessible.

What is stopping us?

What is sometimes perplexing is that we seem to take pride in a general lack of accessibility in science. Colloquialism in papers is strongly discouraged, individual fields have their own bizarre lexicons of words only they would ever possible use, and we write in this perplexing scientific style seemingly to make content as inaccessible as possible; or at least to only appeal to those in our immediate field who have a substantial understanding of the topic anyway.

As a personal example, my girlfriend is German, and a political scientist by training. She speaks pretty good English (better than mein German..), and for some bizarre reason has made a valiant effort to actually read some of my published research. Now, it’s all Open Access, but usually it takes about 30 seconds for the headache signs to begin, and instead I direct her to media coverage or my own blog posts about the work instead.

So I kinda failed here, and it’s based on how I’ve been trained, and how we’re all trained as scientists. I didn’t write my papers for a ‘non-specialist’ audience. As in, I didn’t make them accessible to anyone unless they were already fairly proficient in the field. Thinking about how research is communicated often happens after we have already published an article, rather than at the offset.

Thinking to the future

I think we could do a lot better at this as a collective by embedding communications strategies in our activities as researchers right from the beginning of new projects. Blogging, giving public talks, tweeting, translating, sending to relevant communities with non-specialist summaries, getting feedback and seeing how you can improve things in terms of accessibility as a process could be very powerful in improving the understanding of different aspects of research projects. Has anyone written a handbook for researchers in ‘Making Science Accessible’ yet? that would be sweet.

This is important for scientists across different fields too, in order to increase cross-disciplinary research. I’m a geologist/palaeontologist by training. This means that I’m a non-specialist in every other field by default, and would probably bust a blood vessel trying to read the latest in regenerative medicine or biotechnology. Making research more accessible could be a great way to help decrease barriers between different sub-fields and really open up opportunities for stronger collaborative research across fields.

For me, I blogged about most of my research papers in an attempt to convey the key findings, the importance, and the context of the research, and this is something which many researchers are doing now and it’s amazing! And if people want to learn more, then the papers are Open, and the opportunity for them to do so is there. You don’t get this with privileged access, as you don’t have access to the primary research unless you can pay. But I’m still not sure if this goes far enough by a long way.

So yeah, while Open Access is still beset by implementation problems, it opens up a whole new set of issues about what do we do with this information to maximise its accessibility and potential.

Answers on the back of a postcard.

*I’m actually writing this in Cambodia at the moment, and it’s taking me forever due to the crappy internet connection. And trying to download research papers via Imperial College’s VPN, or ones that are OA, is taking so long it makes the publishing process look fast.

Interesting post. I agree with a lot of it. I wonder though how many non scientists want to read a full paper? In my expereience not many, most would rather read a well written summary blog. In which case did you really fail if you could easily direct your girlfriend to blog posts? On the other hand maybe you are right some of those people arent keen to read a full paper because they are inaccessible.

This is an interesting question. We don’t know how many non-scientists want to read a full paper, because most of them simply can’t, which we can conflate as evidence for them not wanting to. In my experience, non-scientists usually want to try and at least attempt to read the original source for research-related things. People are always more curious than we give them credit for. Blog posts are good as summaries, but never a replacement for getting fully engrossed in a good research article! 🙂