Peer review does not have a ‘gold standard’, but does it need one?

However ill-defined it may be, the peer-review process is still the gold standard that will continue to drive scholarly publication. (source)

I’m not really sure what this means. It sounds like, ‘no-one knows what peer review really is, but we’ll maintain it at the core of research anyway’..

The same for..

While it is not a perfect process, traditional peer review remains the gold standard for evaluating and selecting quality scientific publications. (source)

We keep repeating this mantra in academia as a sort of shoulder shrug. My feeling on the matter is this:

“How can something exclusive, secretive, and irreproducible be considered to be objective? How can something exclusive, secretive, and irreproducible be considered as a ‘gold standard’ of any sort?” (source)

Because of this, we have absolutely no idea what goes into the hyperdiverse process of peer review. We know that when something comes out, it is conferred the status and stamp of ‘peer reviewed’. For some bizarrely unscientific reason, we then maintain this as a pseudo-standard for validity and quality. Except we don’t actually have any knowledge of the process that led to this, because that’s how peer review largely works. Academic logic at its finest.

Peer review fails peer review, and its own test of integrity and validation, and is one of the greatest ironies of the academic world.

What we should be thinking about instead is how to inject some science into our primary method of ‘scientific validation’. Like any human endeavor, it will always be at least partially subjective, but that doesn’t mean we can try to eliminate many of the well-documented problems it has (see ‘Problems with peer review‘ here).

Does peer review need a standard?

I wrote about how peer review in general seems to be lacking any form of standardisation recently, due to its inherent traits of being exclusive, secretive, and irreproducible. We as the scientific community should be thinking more about the management, functionality, and process of peer review. It is our collective responsibility that peer review is held to the same high standards of integrity that we do for research.

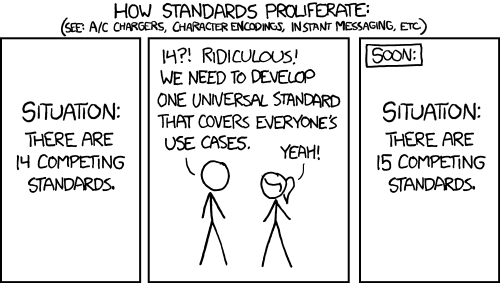

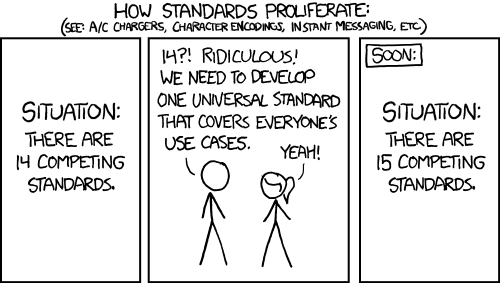

Until we can do this, I don’t think we should keep pretending that peer review is any sort of ‘gold standard’, because we just don’t have any evidence to support this. However, what we don’t want to create is another standard, if some already exist, as that would just be redundant.

Some things that exist already

- Code of Conduct and best practice guidelines for journal editors (link)

- COPE ethical guidelines for peer reviewers (link)

- Peer Reviewers Openness Initiative (link)

- A guide to peer review, British Ecological Society (link)

- Referee guidelines, Institute of Physics (link)

The COPE guidelines probably come closest to what we have as a standard: “The COPE Ethical Guidelines for Peer Reviewers set out the basic principles and standards to which all peer reviewers should adhere during the peer review process.“

To me, these are mostly sets of principles or guidelines to ‘do a good job’. They don’t quite meet the idea of a ‘standard’, as they don’t define a level of technical quality or attainment that can be used for comparative purposes. Which is useful, say, for examining the utility and functionality of peer review. Guidelines also appear to be a bit too general and open to interpretation at times. The power of a standard comes in its specificity, which doesn’t really work too well for a process as diverse as peer review.

I think the COPE guidelines are great, but that we could use them as the basis for something more. For example, having each item in the guidelines as a checklist for referees. Here, each peer review would have to satisfy a certain ‘quality’ threshold before it is accepted. This would, in my eyes, make it more of a ‘technical standard‘ (i.e., an operational checklist). Ultimately, this would also progress it towards conforming to an ‘open standard‘.

The main issue that arises is that an actual standard might stifle diversity and creativity in peer review. This is certainly not a good thing.

Yes, what we need is MORE bureaucracy..

Academics hate rules. A standard or set of guidelines creates a rigid system that research suffers far too much from already. The idea of implementing a standard for something as inherently diverse as peer review has potential desirable outcomes, such as increasing overall quality. But this might come at the cost of becoming too narrow or rigid a process. What we need is for peer review to remain flexible for different communities, but to still perform the basic tasks we hold it to.

Really, the issue lies with pretending that peer review has any sort of standard as a process at all. The quality of peer review is impossible to assess, and therefore we can rarely see whether it has attained a certain threshold or not. It is impossible to quantify, again due to it being a hidden process, which means that we cannot use it for comparative purposes.

So when people say ‘gold standard’ of peer review, I don’t really know what that means. It’s more like holding on to the concept of it as this magical process of validation and gatekeeping, when really we have very little idea if it actually does these effectively. In fact, much of the evidence suggests that peer review fails to even meet the most basic ideals that we hold it to. So practically, I think we need to explicitly stop calling peer review a ‘gold standard’ of any sort. But does this mean it needs to become ‘standardised’?

An alternative solution

All of these guidelines and principles represent more bureaucracy in an already bloated bureaucratic academia. Instead, we could and should be teaching students the reasons why peer review is important. Get this right, and you won’t need external guidelines, as they’ll be embedded as a culture anyway.

What’s better: Having to go through a checklist for each peer review, or knowing in advance how to perform a high quality peer review?

So instead of guidelines or standards, what we need is better training in the why of peer review. Imagine this as a couple of very simple examples:

- Why: High quality research is supposed to be reproducible;

- Consequence: Referees request code and data etc. be made available during peer review to test results;

- Why: Published research is supposed to be valid;

- Consequence: Referees make sure conclusions are supported by results;

- Consequence: Referees make sure analyses have been conducted correctly;

- Why: Published research is supposed to be high quality;

- Consequence: Referees make sure research passes basic tests of integrity;

- Consequence: Peer review factors into objective assessments of research quality.

These translations of principles to practices shows how teaching students/researchers why can lead to automatically conducting peer review at a higher level. How much better is this than telling students they have to do it as “part of their academic duty”.

Practical steps

Great initiatives like the Publons Academy are doing much to teach students and researchers the practical steps in doing a peer review. Even I’ve built a peer review template with Authorea as a sort of ‘checklist’ for things you should be looking to cover during a peer review. Both of these are more hands on approaches, but do little to convey why doing rigorous peer review is important.

I think naturally this will see a shift towards open peer review too, something which is already happening, as openness forms one of the cornerstones of reproducible and high quality research. By opening up the process, we can also begin to analyse and quantify it. This forms the basis for creating an actual ‘gold standard’ for peer review.

One thought on “Peer review does not have a ‘gold standard’, but does it need one?”