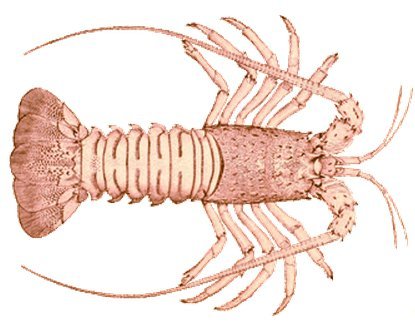

For the spotted spiny lobster, size does matter

In a great many species, females exhibit preferences for larger males – including that world-dominating species Homo sapiens (though a recent PLoS ONE study reveals the effect is only modest in actual couples). Certainly in the marine environment, choices such as this correspond to greater fitness in a species, with larger individuals being more fertile than smaller ones. Fishing can disrupt mating systems by altering population size structure – that is, causing a shift to smaller individuals. This is a particular problem when populations are fragmented (due to patchy habitats), as there are already limits on partner choice. Lobsters populations are often fragmented and with this in mind, Drs Denice Robertson and Mark Butler have investigated the size preferences of the spotted spiny lobster (Panulirus guttatus).

Using 120 lobsters from the Florida Quays, they found that while all males were equally keen to court the lady lobsters, small females fled from their attentions and larger ones drove them off – quite the case of hard to get! Monitoring mating is no easy process as mating events are rare enough that witnessing them requires many hours of observation. So, perhaps to avoid many caffeine-filled nights in the lab, or the need to trawl through an interminable quantity of video footage, Robertson and Butler developed a novel method of determining which lucky Romeo had mated with a female:

Combinations of small, medium and large males were placed in the same tank as a female loobster to determine her mate preferences. Successful mating could be identified by the presence of a spermatophore – a pouch in which sperm are passed to the female after release from another aptly named piece of anatomy, the gonopore (“gonad opening”). Males have two of these between the last pair of walking legs and through a somewhat cringeworthy process of blocking the right (small), left (medium) or neither (large) gonopore with epoxy resin – I know, you were warned! – Robertson and Butler were able to identify the size of the successful male from the spermatophore’s position. It would stick to the left, right or both sides of the female if the right, left or neither gonopore was blocked, and voila! No need for paternal testing!

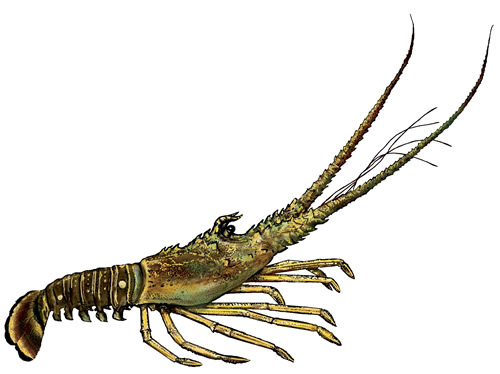

While males had no preference for partner size, females chose males larger than themselves in a whopping 92% of cases. Those that settled for smaller lobsters had significantly lower fertilisation success, with fewer eggs being fertilised when large females mated with small males. This low rate of success is a consequence of the fitness disadvantage held by smaller individuals known as sperm limitation. Sperm limitation is not commonly associated with species that transfer gametes directly, but there is increasing evidence for it in spiny lobsters. For example, in the Caribbean spiny lobster (P. argus, also a Florida Quays resident) males vary the amount of ejaculate according to female size – so it is not just male size that influences fertilisation success!

Florida Quays is not a heavily fished area, but the prevalence of sperm limitation in these species means that fishing activity has the potential to severely impact spiny lobster populations in areas that are, and indeed in Florida Quays if fishing pressure increases.

References:

Denice N Robertson and Butler MJ IV (2013) Mate choice and sperm limitation in the spotted spiny lobster, Panulirus guttatus. Marine Biology Research, 9:1, 69-76.

MacDiarmid B and Butler MJ IV (1999) Sperm economy and limitation in spiny lobsters. Behavioural Ecology and Sociobiology. Vol. 46, No. 1, pp. 14-24.

Stulp G, Buunk AP, Pollet TV, Nettle D and Verhulst S (2013) Are Human Mating Preferences with Respect to Height Reflected in Actual Pairings? PLoS ONE 8 (1): e54186.

The Miami Spiny Lobster Tournament… mini season 2013