Virtual Palaeontology – taking science communication to the next level

I recently wrote a small series about how geoscientists can become more effective communicators of scientific knowledge to the general public, and the pitfalls and issues associated with this. The overall strategy revolved around using the right type of language, along with a context and narrative to create relevant stories, but above all this, to just go out there and do it! That’s exactly what Imran Rahman has done, except he’s gone a huge step further taken palaeontology and science communication into the digital age!

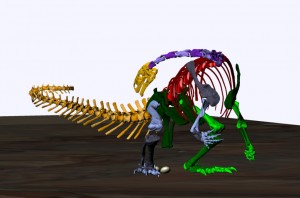

In a new paper, Imran, along with two others, demonstrates the value of using ‘virtual fossils’ as a tool for science communication, I guess specifically to palaeontology, but there’s no reason why other fields cannot adopt (or already have done) similar methods. The use of digital palaeontology has been ongoing for quite a while now within the scientific community, with virtual reconstructions ranging from hadrosaur skulls using CT-scanning (computed tomography – the same process they use to peer inside you in hosptials) to early molluscs and arthropods using a process known as serial grinding. As such, it is pervasive throughout palaeontology, but has never really taken flight and been introduced to the public as an engagement resource.

Imran wasn’t content though just with digitally communicating any old fossils – virtual reconstruction can breathe life into rare and fragile specimens, and allow people to interact with them in ways previously unknown. Digital reconstructions provide accurate 3-dimensional representations of fossils, and you can fiddle with them in any manner of ways, including ‘peeling away the layers’ to look at their internal morphology. Pretty freaky. There’s actually some free software for playing with fossils like this, which I kinda have to plug as my supervisor, Mark Sutton, was the one who developed it.

Taking it a further step, with the onset of 3D printing it is now possible to take this digital reconstructions and create synthetic and highly-detailed models that can provide great physical displays, for example in museums, along with digital reconstructions and perhaps the original fossils if possible – how cool would that be?! It would allow communities to interact with rare or fragile specimens in a new and unique way (and everyone knows the only reason people go to museums is for the fossils, right? Right??). Imagine the effect this can have for blind or visually impaired people too.

Imran pilot tested the application of virtual palaeontology earlier this year at the famous Lapworth Museum of Geology in Birmingham (UK), and established several criteria that would motivate project success:

- Fossils selected to exhibit would have to be 3D originally. This is for the purposes of CT-scanning and subsequent printing of the models.

- Fossils have to be finely-detailed, to be able to convey the important and previously hidden anatomical structures.

- The fossils must be appropriate for CT-scanning, with respect to size and relative density.

-

Imran and his exhibit at the Lapworth Museum (copyright: Imran Rahman)

During the exhibition, as part the University Community Day in June, Imran (along with Russell Garwood, another virtual palaeontology wizard) set up shop with a computer reconstructions on a laptop, a series of 3D models, projections of 3D red-green anaglyph stereos onto a screen (with 3D glasses to visualise properly). Throughout the exhibition, Imran and Russell were visited primarily by parents with young children; the former being more interested in the technologies, and the latter more interested in the model fossils and the 3D glasses, meaning that the duo had to take a two-pronged approach to successfully engage. As such, digital fossils provide a ‘free-choice’ learning opportunity for the general public, and can substantially enhance understanding of complex issues such as evolution and the nature and role of the fossil record. As well as this, they can provide a practical demonstration of how palaeontology isn’t so much about the typical Alan Grant or Ross Geller scenario, but is instead advancing rapidly in parallel and conjunction with external technological developments. Huge kudos to Imran and the others for embracing this, and taking digital science out of the lab and to the public. More in the future please! Just noticed as well, Imran has been awesome enough to put the paper up on his academia.edu webpage, so you can read about this for free!

The British Geological Survey, partnered with several organisations, is currently creating an online catalogue of British type specimens (the specimens upon which taxonomic names are created upon). The rationale behind this project is to increase the global availability of specimens for study, as well as to have a record of specimens which may, unfortunately, deteriorate in quality over time. This is a pretty huge project, and the wealth of data being made available (I think openly for anyone too) is invaluable. There have already been hints that the database may be made available as an open education resource (which you can contribute to if you wish!), but with this advance from Imran et al, the potential for it to be used as a vast science communication resource is undoubtedly a pathway that should be considered. Hint to anyone from the BGS reading this.

This was originally posted at: http://blogs.egu.eu/palaeoblog/2012/12/19/virtual-palaeontology-taking-science-communication-to-the-next-level/

Several years ago I was looking semi-seriously at building a 3d-printer (step-daughter on gap year ; bedroom for office/ workshop space ; but the wife stole the room for her night-school study instead). One motivation was explicitly to be able to make “virtual endocasts” of, for example, the reptile fossils of the Elgin-Lossiemouth sandstones, which classically aren’t there.

One thing that became clear to me is that there is a wide, and confusing, array of file formats available for stages of the process ; a wide and confusing array of programs for collecting / manipulating the data ; and no clear path to designing your toolchain. If I’d been particularly interested in becoming an expert in 3d-printing, that would be great ; but I’m more interested in getting (say) another “Lizzie” out of the rock without destroying the fossil.

Unless things have changed significantly in the last couple of years, there is a definite need for guidance through this morass, otherwise people will get excessively buried in the details.

Some years ago there was a comparable situation with respect to “stitching” photographs together to make large and-or panoramic images. I returned to this more recently and discovered the “Hugin” project, which collapses a toolchain of Open Source elements into a much more coherent whole, which can be easily navigated. Sure, each step has lots! (“!” implying “factorial ” here! (but not here[exclaim]) of options, but the overall path is well established.

That, IMHO, is a step that the 3d-processing world needs to take.