Should we cite preprints?

Recently, Matt Shawkey*, an Associate Professor at the University of Gent, tweeted his opinions about citing preprints in formal research publications, stating that they should not be cited as equivalents to papers that had been peer reviewed. This led to a great deal of interesting discussion around the topic, but scattered all over various Twitter threads. While this discussion has happened many times before, it’s always different as new developments and voices get incorporated, which is great!

The citation of preprints is something of great interest to me, as the founder of PaleorXiv, a preprint server for Palaeontology, and because it seems to be against the direction that academia is generally heading towards (e.g., the NIH is now allowing preprints to be cited in grant applications).

So my super-controversial opinion is that un-reviewed, preliminary documents (preprints) should not be cited in same way as final documents.

— Matthew Shawkey (@mdshawkey) May 13, 2017

Nonetheless, a lot of interesting and controversial discussion points were raised about this issue, and I think are worth trying to bring together coherently, so that we can all learn from them constructively. It’s worth noting in advance that how you perceive the traditional peer review model is an important factor in these discussions, but too complex to address in this post alone. This post is also probably not comprehensive, although I’ve tried to present a decent overview, and definitely not 100% ‘correct’. If anything is missing, please do comment below, especially where I am wrong about something.

What we have to remember though ‘in advance’ is the main reason why preprints exist: They are intended to get the results of research acknowledged and make them rapidly available to others in preliminary form to stimulate discussion and suggestions for revision before/during peer review and publication.

-

Issue: We shouldn’t cite work that hasn’t been peer reviewed

Citing work that hasn’t been peer reviewed has been traditionally seen as a big academic no no, and is definitely the primary problem that gets continuously raised. However, we need to remember that many journals have been more than happy historically to accept ‘personal communication’, conference abstracts, various other ‘grey literature’, and as someone alluded to on Twitter, personal phone calls, as citations, so why should preprints be treated any differently?

If we look at academic re-use statistics, 4 out of the top 5 most cited physics and maths journals are subsections from the arXiv (thanks, Brian Nosek, for this). In Economics, the top cited journal is the NBER Working Papers preprint archive, both according to data from Google Scholar. What this tells us is that research disciplines that have a well-embedded preprint culture see a massive research value in them, even transcending traditional journals in many cases, and does not seem to be causing any major issues in these fields.

A really key point is that citing work without reading it is a form of bad academic practice: responsibility of the citation lies with the citer. Reading a paper as a researcher without evaluating it is also bad academic practice. Evaluating papers is basically a form of peer review, therefore a citation is a sign that we have critically reviewed a paper and decided its value; or at least it should be. After all, evaluating the quality of scientific work is the job of scientists, and should not simply stop because something has a preprint stamp. As Casey Greene said, citations do not “absolve one of the ability to think critically.” We should have enough confidence in ourselves to be able to make these judgement calls, but perhaps just be slightly more wary when it comes to preprints. This is particularly the case for research which we heavily draw upon. It is our collective responsibility to carefully evaluate whether a citation supports a particular point – if we cannot do that, we do not deserve the title of scholar. Now this doesn’t alleviate all potential biases, but then we can’t claim that traditional closed peer review does either in this case if this is our argument, as it is always the same peers doing the review, or at least to random to draw a line between them.

If a preprint was so bad that it was not able to be cited, then we don’t have to cite it. Furthermore, anyone evaluating a preprint who comes to that conclusion and does not leave a comment on the preprint as to how they reached that conclusion is doing the scholarly community, and the public in general, a disservice. The vast majority of preprint services offer comment sections for evaluation, which alleviates a great deal of the issues regarding ‘bad science’ being published. Of course, not everyone uses these functions yet, but we can expect that they will as preprint adoption and open peer evaluation increases.

The inverse is also true in this case, that just because a paper has gone through traditional peer review, does not necessarily mean it has higher standards and is 100% true. If we believe that published papers are immune from the same problems as preprints, we undermine our own ability to conduct research properly.

-

Issue: Non-specialists might read papers that have ‘unverified’ information in and then mis-use it.

Now, this is an interesting and valid concern, and one which is discussed briefly here in the ASAPbio FAQ.

What we also have to remember is that some disciplines have huge preprint sharing cultures, including Physics/Maths (1.2 million, arXiv), Economics (804,000, RePEC), and Applied Social Sciences (732,000, SSRN), and so far they seem to have managed the outflow of information very well. Some existing mitigation methods exist already, such as a simple screening process to block pseudoscience and the spread of misinformation.

In fledgling fields where preprint use is accelerating, such as the Life Sciences, as far as I am aware this has not led to any notable difference in the proliferation of ‘fake news’ or bad science. Of course, this doesn’t mean it couldn’t happen, just that it hasn’t yet. Ignoring the history of other fields is generally bad-practice and just leads to less-informed discussions about these potential issues. We should make sure to use the positive experiences from Physics, Social Sciences, and Economics and make sure that the ways they combat misinformation are also in place on any new preprint servers for other fields.

Even still, this is a problem not just for preprints, but the entire scholarly literature – research is out there, and people will use it in different ways, and often incorrectly. Think autism and vaccines, for example. This happens whether research or any other content is ‘peer reviewed’ or not. We should see this more as an opportunity to engage people with the research process and scholarly communication, rather than belittling people for being non-specialists. Bad actors are going to be bad actors no matter what we tell them or what is published or peer reviewed – the last 12 months of ‘fake news’ and ‘alternative facts’, as well as decades of ‘climate change denial’ and ‘anti-evolutionists’, are testament to that.

In terms of science communication and journalism/reporting, these would benefit greatly from having standards whereby they wait until final versions have been published, just in case. Indeed, most journalists are savvy and respectable enough to recognise these differences. If you want to report on preprints as a communicator, pay attention to any discussion (perhaps via the Altmetric service to track online conversations), and make it clear that you are explicit that the research is preliminary. Journalists frequently do this already when reporting on things like conference talks and proceedings, and the standard should not be any different for preprints.

-

Issue: Citing preprints under-values formal peer review.

While there are always exceptions, peer review generally benefits both authors and articles. By citing a preprint, you are not de-valuing this process. You are simply using your own judgement, while an article is undergoing formal peer review, to decide whether or not to cite an article and the context of that citation. They are not in conflict, they are complimentary.

-

Issue: Citing preprints lowers the standards of scholarship.

A big issue here is that often preprints can change compared to their final published form. For example, there might be changes in taxonomy, additional experiments required to be ran, new analyses to add, all of which can change the discussions and conclusions.

These are all important things to consider, and will vary depending on research community practices. However, one thing which will greatly ease this is simply to have a big ‘Not Peer Reviewed’ stamp on preprints, as most do, which should act as a sort of nudge to be more cautious. No one should rampantly re-use published research in any form without adequate consideration and evaluation anyway (see above), but having this stamp makes it easier to slow things down if needed and know when extra care and evaluation is needed. Something that would also make this much easier for us all is to allow data to be shared alongside preprints, as well as code and other materials, so that results can be rapidly verified, or not, by the research community.

We should also take note that science changes through time, and conclusions alter as new evidence is gathered. The very nature of how we conduct research means that previously published information can be, and often is, over-turned by new results, which is not very different from information changing through article versions. The major difference here though is that preprint version control happens in the open, which is invariably advantageous to all parties.

One of Matt’s points was that while preprints themselves were fine, it was just their citation that was bad practice. This creates a logical conflict (to me at least), as if the information contained within was fine, then why not cite it appropriately where it is re-used? If it were of such bad quality for re-use, don’t cite it, and indicate why. As Ethan White said recently, “There are good preprints and bad preprints, good reports and bad reports, good data and bad data, good software and bad software, and good papers and bad papers.” As before, it is up to the research community and their professional judgments to decide whether or not to cite any research object.

A rule of thumb, for now, that might help with this is if an author, and the reviewers of their article, think it is appropriate for them to cite a preprint then they should be allowed to do so as they would any other article.

-

Issue: Preprint availability creates conflicting articles

Preprints can change. Preprints published on the arXiv, biorXiv, with the Center for Open Science all have version control that allow preprints to either be updated with new versions or linked through to final published versions. These are usually clearly labeled and can even be cited as separate versions. Using DOIs combined with revision dates makes this a lot easier, as well as simple author/title matching algorithms. Furthermore, preprints are largely on Google Scholar now too, and thankfully this is smart enough to merge records where matches (or ‘conflicts’) are found.

Instead, what we should be recognising instead of this simple technical non-issue, is the immense value having early versions of articles out can be (in the vast majority of cases). Especially, for example, to younger researchers, who want to escape the often unbearably long publication times of journals and demonstrate their research to potential employers. Or in fast moving and highly competitive research fields, where establishing discovery priority can be extremely important.

-

Issue: What happens to preprints that never get published

Well, papers never get published for a multitude of reasons. Also, a lot of bad science gets published, and there is no definitive boundary between ‘unpublished and wrong’ and ‘published and correct’, as we might like to think. Instead, it’s more of a huge continuum that varies massively between publishing cultures and disciplines.

If a preprint never gets published, it can still be useful in getting information out there and retaining the priority of an idea. However, if you find an article that has been published as a preprint for a long time but never formally published, this might be an indicator to be extra careful. Here, checking article re-use and commentary is essential prior to any personal re-use. As before, a simple exercise of judgment solves a lot, for yourself and for non-specialists.

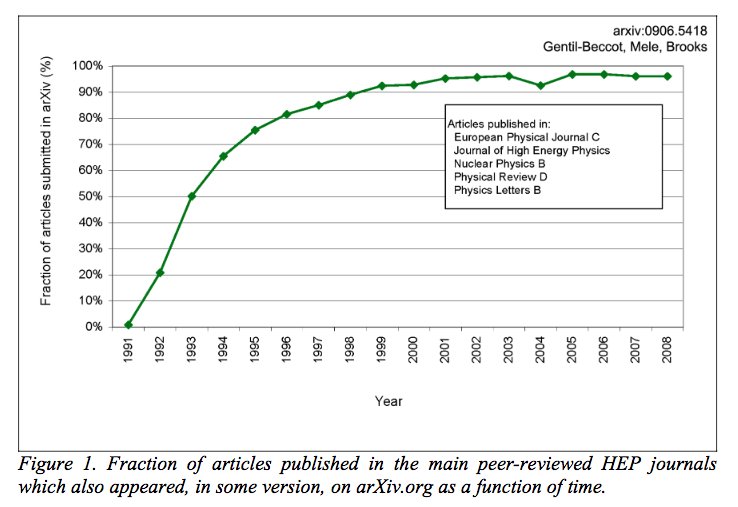

However, as Lenny Teytelman pointed out, in the last 20 years nearly 100% of articles published in the arXiv section on Higher Energy Physics are also published in HEP journals, which suggests that this might be a relatively minor issue, at least in this field (i.e., most preprints are ultimately published).

A somewhat relevant tangent

One thing which keeps popping up on Twitter discussions like the ones that inspired this post, and I have to call out here, is the constant “Well my experience is x, y, and z, and therefore there is not an issue..” in one form or another, and in particular from those in a position of massive privilege. I’m getting sick and tired of this bullshit lack of empathy and use of ‘anecdata’ as if it was anything meaningful. It’s counter-productive, non-scientific, and completely undermines people who have different experiences or come from completely disparate walks of life. Twitter also makes these exchanges intolerably toneless, and often seem unnecessarily aggressive. Let’s keep things civil, professional, constructive, and where possible informed by real evidence and data – you know, like peer review should be. Some times, people also don’t need to know your opinion, and that’s totally okay.

Wrapping it up

At the end of this all, we have to remember that no system is perfect, especially in scholarly publishing. What we should all be doing is making evidence-informed evaluations of processes in order to decide what is best for all members of our community. Especially those who are under-represented or marginalised. We have to listen to a diversity of voices and experiences, and use these to make sure that the processes and tools we advocate for are grounded in the principles of fairness and equity, not reinforcement of privilege or the status quo. This means we have to look at the costs versus benefits, and where we don’t have data, make decisions to either gather those data, or proceed in a way where risk is minimalised and potential gain is maximised.

In terms of solutions to all of this, I think there are several simple points to finish off:

- If you’re going to cite a preprint, make it clear that it’s a preprint in the reference list, and in the main text if possible.

- If you’re going to publish a preprint, make it clear that it’s a preprint (most servers already do this).

- Preprint servers need version control. The vast majority do already.

- Community commenting on preprints is essential, especially to combat potential mis-information.

- Preprints compliment, not undermine, the existence of traditional peer review and journals.

- Preprints are gaining increasing high-level support globally. Just like with Open Access and Open Data, this stuff is happening, so best to engage with it constructively in a manner that benefits your community.

- Exercise judgement when it comes to publishing, citing, and re-using preprints.

- If preprint citation is happening anyway, rather than fighting against it, let’s spend our collective effort on working to support and improve the process. Find what works in other fields, and apply that to ourselves.

Ultimately though, the answer is YES.

——————————————–

*Kudos to Matt, who engaged with these discussions with civility despite a clash of opinions. Matt is a colleague, whose inter-disciplinary research includes palaeontology, and he was very helpful as an Editor at PLOS ONE for me recently in helping to support my requests to open up my review report, which I greatly appreciate.

Some further reading (please suggest more if needed)

Thanks for writing this up, Jon. It is an opinion piece and it captures the pro-preprint-citation side pretty well, but not the anti-preprint citation side. I have no problem with preprints in a general sense, but where I differ with you is on their function. In my view they are a neat way to get additional feedback on a manuscript before or during the traditional peer review process. They should thus not be viewed as anything but preliminary documents. Everything in them from the data (“woops, I copy-pasted a row wrong!”) to the interpretation (“I performed an additional control experiment and it turns out my results are an artifact”) is subject to change. Thus, it is simply premature to cite them. Of course, published documents sometimes change too. But after a round or two of peer review this is less likely.

The 2nd major difference in viewpoint I have is on the definition of peer review. A common point of view is that the citer’s judgement on the soundness of the paper is sufficient for peer review, since after all they are a peer and they are reviewing it. This argument sounds clever and commonsensical on the surface, but less so when phrased as “my peer review alone is as good as, or better than, my peer review plus the peer review of others.” Then it just sounds narcissistic and disparaging of one’s colleagues. Of course, peer review does not alleviate one of the need to read and judge a paper for yourself before citing it. But it is hard to argue that one set of eyes on a paper is as good as three or more.

The argument is made that this additional peer review can be found in the comments sections of the preprint archive. The problem here can be made clear by actually looking at these comment sections, which are either empty or filled with endless retweets of the authors announcing the deposition of the preprint (I call this the “Wu Tang Forever” problem, because that album is filled w endless rhymes about the fact that they have now dropped the album.) Perhaps this will change in the future (and I have serious doubts about that), but for now it is not a meaningful substitute for traditional peer review.

So is one disrespecting traditional peer review by citing a preprint? I can’t discern intention, but in effect one is stating, as above, that your judgement alone is sufficient, and the judgements of others are not needed. This implies that traditional peer review is not needed. It is hard to see how this is not disrespectful of the work that one and one’s colleagues do to assess work. Many have made the argument that a citation is just to guide the reader, but by citing something you are giving it stature as a legitimate source. The ephemeral nature of preprints does not confer this status on them.

Another argument is that citations to ‘grey literature’ and personal communications are allowed in some journals. I have come around to the idea that citing non-peer reviewed sources such as hunting regulations cannot be avoided in some cases. But are pers. comms really the company that you want to keep? Do you want to expand the amount of weak references in the literature?

I also think that comparisons to the successful use of preprints in e.g. physics are misguided. For one, physics is a much smaller community than biology. And my impression is that the science itself is less messy and easier to judge than biology. This is not to say that it could not work in biology, but right now it is not working (see:empty comments sections) and it is premature to start citing before the ecosystem itself is functional.

Thank you Matt and Jon for the discussion.

Question for Matt. Suppose you used Benjamin Schwessinger’s protocol “High quality DNA from Fungi for long read sequencing e.g. PacBio” (https://www.protocols.io/view/High-quality-DNA-from-Fungi-for-long-read-sequenci-ewtbfen). It’s an unpublished method, available as a preprint on protocols.io and successfully used by many scientists. Benjamin has kindly shared it for the benefit of the community.

Now, you Matt are writing a manuscript reporting on the sequencing of the DNA that you obtained using Benjamin’s preprint. Do you not cite it because it hasn’t been peer-reviewed?

Isn’t your citation of it and successful utilization of the technique the ultimate post-publication peer review that lets everyone know that the protocol works? Isn’t it way more of a signal that Benjamin’s preprint method works than if you simply read it as a reviewer instead of using it?

Lenny, good question. It may not answer it, but the truth is I would not use an unpublished protocol I found on the internet. time and resources are too scarce.

It’s a lab you know. Your graduate student knows that postdoc. Talked at a conference. Your student used it because the protocol is superior to the one currently used for DNA extraction in your lab.

Now your options are to cite the 40-step protocol that Benjamin has carefully documented and shared (now on version10), or to just say “unpublished”. What is best for the community?

I like how you finish with “What is best for the community?” I’m not saying it applies here or to anyone specifically, but many academics to seem to perpetually suffer from a lack of empathy, and focus their arguments on exclusively selfish reasoning. Thinking about what’s best for others is always the best approach, in my view.

“We thank Benjamin for use of his unpublished protocol, available at this link”

How is that any different to simply having a citation to the formal article (complete with DOI) and a note stating that it’s a preprint?

Hi Matt,

Thanks for taking the time to respond here, much appreciated. Just to start – this is not an opinion piece, this was a critical overview of the issues combined with a solution-oriented approach to moving things forward. There are parts of it that are the opinion of me, my peers, and those who disagree with me, so is not exactly one-sided. I’ll try and address your points based on paragraph number.

1. This is a summary of the points I made in ‘Issue: We shouldn’t cite work that hasn’t been peer reviewed’, and as for your conclusion, I addressed that here: “One of Matt’s points was that while preprints themselves were fine, it was just their citation that was bad practice. This creates a logical conflict (to me at least), as if the information contained within was fine, then why not cite it appropriately where it is re-used? If it were of such bad quality for re-use, don’t cite it, and indicate why. As Ethan White said recently, “There are good preprints and bad preprints, good reports and bad reports, good data and bad data, good software and bad software, and good papers and bad papers.” As before, it is up to the research community and their professional judgments to decide whether or not to cite any research object.”, and further summarised in the final points: “Exercise judgement when it comes to publishing, citing, and re-using preprints.”

2. This is addressed in the summary points too: “Preprints compliment, not undermine, the existence of traditional peer review and journals.” and also the section “Issue: Citing preprints under-values formal peer review. – While there are always exceptions, peer review generally benefits both authors and articles. By citing a preprint, you are not de-valuing this process. You are simply using your own judgement, while an article is undergoing formal peer review, to decide whether or not to cite an article and the context of that citation. They are not in conflict, they are complimentary.” So no one is calling for ‘informal preprint evaluation’ to replace formal peer review, or comparing the relative quality of either process. The eye analogy kind of breaks down due to the simple fact that not all peer reviews are equal. You could have three terrible reviews or one great peer review. You could also have 3 great peer reviews or no peer review. The process is hypervariable, and we shouldn’t allow counts of things that cannot be directly compared (each peer review is unique) cloud our judgments here.

3. I love the ‘Wu Tang Forever’ title for this problem, and am going to steal that too (with attribution 😉 ). And I agree that at the present, public commenting and evaluation is still in its relative infancy. A useful recent post on some stats for this is here: https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2017/04/27/stop-commenting-already/ However, as mentioned above, commenting on preprints is a compliment to, not a replacement for, formal peer review.

4. Judgment does not have to be a personal thing, and rarely is. Indeed, as others have commented, it is about making an informed decision based on the best available information to you. Again, this is not a replacement for formal peer review, but a compliment to it, remembering that preprints are designed for rapid communication and feedback while the research is going through formal publication channels. So we should stop making the either/or debate central to our discussions on this, and focus on the fact that they are complimentary processes. I think this is really important, and perhaps worth a lot more discussion in the future. As for legitimacy, this is addressed several times in the post – a combination of appropriate citation and version control alleviates this entirely.

5. The real question here is what is the harm of citing grey literature. As others have mentioned, the citing of preprints and various other grey literature is fairly commonplace in a range of fields, and they don’t seem to be collapsing in on themselves. And I think referring to preprints as ‘weak’ again is not the best thing to be saying about our colleague’s work, and refers to other points about being able to making adequate judgment calls ourselves.

6. I don’t think using the experiences and others is misguided, either. I think they are learning opportunities. Understand the models and the community structure, what works and what doesn’t work, and apply that to our own disciplines. As I mentioned in the PaleorXiv post, “Palaeontology is a very niche community and research field. What has worked for the arXiv, socarXiv, LawarXiv etc. won’t necessarily be what is best for us. ” – http://fossilsandshit.com/paleorxiv-now-open-for-submissions/ But this does not mean we should neglect their experiences entirely simply because it’s a different discipline.

I think this addresses most of your points? Of course, there will be ideological/cultural/experiences-based differences that we all have that will be guiding our thoughts on this. My main feeling is that we, as researchers, should not be afraid to experiment, find what works and what doesn’t, and use data and experiences to continuously evaluate and refine our scholarly practices. At least, so long as this does not increase the risks for those groups who are already systemically under-privileged. I’m probably more adventurous than many in this respect, and embed most of my thinking in these matters in factors like transparency and accountability, and principles of fairness and equality. As such, I think my final 8 points remain well-supported for now, but that’s not to say that they are universally correct!

Thanks for the discussion, Matt – I owe you a beer one day for all this 🙂 (maybe a pitcher then..)

Jon

Hi Matt,

I think we’ve covered most of these debate points in the original twitter discussion, but I want to discuss the claims you make about Wu Tang Forever. The distance between your comment and how I interpret the album parallels how differently we feel about peer review and pre-prints. You said:

> I call this the “Wu Tang Forever” problem, because that album is filled w endless rhymes about the fact that they have now dropped the album.

For anyone reading who thinks this is a pithy reference, it’s not. It just makes it clear that the person saying it hasn’t listened.

Wu Tang Forever is, in my opinion, one of the great works of art of the 20th Century. From the outset it was designed to be aggressively domineering about the Clan’s mastery of the hip-hop scene. They pressed it as a double album to prove they could lace 29 tracks effortlessly and have the entire thing be groundbreaking, while most artists who ever tried a double album before had failed miserably. The lead single was a snub to all the assumptions the industry at the time had about what could be a good track – 9 verses with no chorus, nearly 6m minutes of constant flow. At the same time, it fused cryptic slang with layers of hidden meaning and rhyme scheme experimentation that I don’t think had been seen before.

Far from being largely about the fact that the album itself had dropped, I think these are the key themes (among many less prominent, but equally poignant others):

1. The change in the nature of hip-hop and the community that grew around it as a result of Wu Tang’s previous work.

2. Detailing the brutal life experiences that led them to their current perspectives.

3. Espousing the Five Percent Nation’s philosophy and weaving it with their previous perspectives.

4. Baring the paranoia the entire group had developed as a result of their success as an honest expression of self doubt, but simultaneously reinforcing that they could never be pushed aside by any challengers, real or imagined.

5. Lucid criticism and concern about the political and cultural realities of the world.

Granted, the album refers to itself several times in the classic braggadocio style, but always in the context of one of the themes above and certainly not to the detriment of the album.

Here’s one example verse to show the depth of lyricism on the album:

> Fusion of the five elements, to search for the higher intelligence

> Women walk around celibate, livin’ irrelevant

> The most benelovent king, communicatin’ through your dreams

> Mental pictures been painted, Allah’s heard and seen

> everywhere, throughout your surroundin’ atmosphere

> Troposphere, thermosphere, stratosphere

> Can you imagine from one single idea, everything appeared here

> Understanding makes my truth, crystal clear

> Innocent black immigrants locked in housing tenemants

> Eighty-Five percent tenants depend on welfare recipients

> Stapleton’s been stamped as a concentration camp

> At night I walk through, third eye is bright as a street lamp

> Electric microbes, robotic probes

> Taking telescope pictures of globe, babies getting pierced with microchips

> stuffed inside their earlobes, then examinated

> Blood contaminated, vaccinated, lives fabricated

> Exaggerated authorization, Food and Drug Administration

> Testin poison in prison population

> My occupation to stop the innauguration of Satan

> Some claim that it was Reagan, so I come to slay men

> like Bartholemew, cause every particle is physical article

> was diabolical to the last visible molecule

> A space night like Rom, consume planets like Unicron

> Blasting photon bombs from the arm like Galvatron

– The RZA, Impossible

In this verse RZA establishes that he now draws his worldview from the Five Percent. He expresses his awe at the complexity of the world, and his disgust at the ways people are systematically abused, oppressed and controlled. In one verse he references multiple branches of science, the Qur’an and the Bible, and the Transformers. Like most preprints, it’s a valid contribution to the corpus of humanity, and not something to be dismissed.

Here’s the thing: if you listened to Wu Tang Forever and came away thinking “wow all they’ve got to say is that they dropped another album”, I can’t help but think you’re reading the opinions being shared in this conversation about preprint citation with the same level of casual disregard for meaning. In other words, even if someone made the perfect argument for preprint citation, I don’t believe you’d entertain it.

It’s a good album, but not as good as enter the wu tang. Music is less varied and it has less memorable lines. But I appreciate your passion.

Hey Matt,

Just to follow up, is this your final say on things? Rik mentioned “In other words, even if someone made the perfect argument for preprint citation, I don’t believe you’d entertain it.”, and my long, and still most likely imperfect, response to your comments remains unchallenged on here yet. If there’s more discussion to have, I welcome it from you and all others! But if this is it, please don’t feel ashamed to take a step back and consider that the ‘other side’ might have some valid support for their points 🙂

Cheers!

Jon

Jon- I still disagree (although I think your points are not unreasonable), for two reasons (and probably more):

1. Citing something is not simply a form of peer review. it is an indication that a paper is a valid source of information. Once something is cited, for good or bad, it is now a part of the literature. So you are doing much more than peer reviewing a paper by citing it- you are acting as judge, jury and executioner of its fitness for the literature. In traditional peer review, you can act as jury (by reviewing it as part of a group), or judge (editing the paper) or executioner (by choosing to cite or not). In my opinion being all three is too much responsibility for one person.

2. Of course there is a lot of variation in traditional peer review, and it can be improved. But, as above, throwing it out by citing papers before they are reviewed is not the answer. Given point 1, I don’t see how you can say that citing preprints supplements peer review. something post-publication could be a reasonable, albeit highly problematic, supplement. Or potentially a working system of open peer review where people actually make comments. the “wu tang forever” problem is real.

As a sidenote, “high voltage” by ac/dc is one of my favorite albums, and one of the greatest works of art of the 20th century, but if the situation came along that was analogous to having one song that nearly ruins the whole album, I would gladly refer to it as the “high voltage problem”

Hey Matt,

1. I think you’re fundamentally incorrect here, as Jordan has also argued above: “Citation measures importance. It does not establish validity.” By conflating the two, you’re exposing the weakness of your arguments here. If you are not critical when you are citing, then you’re a bad researcher. If you’re critical analysis is not a ‘form’ of peer review, then I don’t know what peer review fundamentally is as a process in your view. I would suggest reading this again and comparing it to what you state: “A really key point is that citing work without reading it is a form of bad academic practice: responsibility of the citation lies with the citer. Reading a paper as a researcher without evaluating it is also bad academic practice. Evaluating papers is basically a form of peer review, therefore a citation is a sign that we have critically reviewed a paper and decided its value; or at least it should be.”

You are absolutely correct that you are the judge, and hence the point I keep having to reiterate about using your own judgment in these cases rather than alleviating responsibility to do so. So many other commenters have told stories of how they exercise their own judgment like this, as they see it as part of their profession. I see no reason why you can’t do the same, and have more confidence in your own skills and those of your colleagues. Anything else, as many have also stated, is rather bad academic practice. I don’t really understand your final point, it seems to state that no single person can fulfill all three ‘traits’ required for a traditional peer review, which undermines your own arguments in a way.

2. Again, no one is asking for anything to be thrown out. I’ve now asked repeatedly for this straw man argument to stop being used. I think referencing the ‘Wu Tang forever problem’ again after you got so eloquently served by Rik is probably not the best idea here either. I am fully aware of the limits and drawbacks of traditional peer review (eg herelse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2017/04/12/what-are-the-barriers-to-post-publication-peer-review/” target=”_blank”>here, here, and here.) But as you can see, no one is saying ‘throw peer review out’. What we are doing are thinking about ways to improve it.

This is getting to the point now where I’m having to repeat myself over and over to refute the same argument points. As I suggested before, I doubt we are going to come to any sort of reasonable conclusion here between ‘camps’ with this sort of behaviour. You’ve given me plenty to think about, but I’m quite sure that for the most part at least, the arguments presented here, and overwhelmingly supported by those who have engaged with this discussion, are pretty solid still, and my final summary points still stand.

Interesting – thanks. In linguistics, preprints and grey literature are cited all the time, and there was recently a discussion on the linguistics editors’ list about it, concluding that it is no problem. On the other hand, at the risk of anecdata, I’ve repeatedly had the experience that copy-editors and production editors don’t like it, even to the point of trying to get rid of it entirely (despite none of the reviewers or the editor having a problem with it). Now, I’m still a fan of traditional peer review, but I don’t think it should be a precondition for citation. The function of citation is surely to acknowledge ideas and results and give credit where it’s due, and restricting it to only peer-reviewed work makes that more difficult.

Hi George,

Thanks for giving is a linguistics perspective. Is there a prevalence of preprint usage within the linguistics community at all, or is it a fairly new phenomenon?

Jon

Definitely not new – check out Lingbuzz…

https://ling.auf.net/

Well, there we have it then! 6000 linguistics preprints, very nice.

I think many of the arguments in the piece are more relevant to someone who is operating within (traditional) disciplinary boundaries. For interdisciplinary research an individual researcher is more likely to be familiar with *arguments* and *theories*, but perhaps not methods. Therefore they are unlikely to be in a position to critically evaluate all of the science in a preprint outside of their area of expertise/training. When incorporating lines of evidence from outside of their area, they are likely to need to lean on the expertise of peer reviewers, as expressed in the form of an accepted paper.

My research (indeed many people’s) touches on climate change without being a climate change researcher. I may need to support a statement to the effect it will get wetter, warmer, more flooding, more drought etc in my discussion or intro. I can understand enough to follow papers and see conclusions are supported by data (it is internally consistent). However, I have neither the expertise or the time/will to fully explore the methodological complexities of ensemble global climate modelling, downscaling etc, to a sufficient level to be able to competently assess an entire specialist climate paper methods. I therefore have to rely on a “stamp of approval” in the form the paper has been reviewed by people who do. This is just one easy to explain example. Yes, they could still be wrong, but I take the view that if I need to stick my hand in a box and there are two, one of which has been pronounced free of snakes by an expert in finding snakes, and one which is unknown, I’m probably going with snake expert even if they may be fallible.

Furthermore, and this may be exposing my shoddy scholarship, if I read a paper I’ll typically do it in 20-30min. If I am reviewing a paper I’ll read it over about an hour, put it down for a week or so, go back, read it through with a fine tooth comb over a couple of hours, reassess and write my report. I’d guess half a day or more total work to properly peer review. Reading is not ‘peer reviewing’ except in a reductionist, semantic sense.

What all this means is I would never cite a preprint, except in the instance it was firmly in the disciplinary sphere(s) I feel intimately knowledgeable of, such that I can critically assess every aspect almost by instinct.

Hey Simon,

Thanks for the super interesting comment! I was just chatting about this the other day with a colleague too who works on the fringe between computer science and palaeontology. They sort of came to the same conclusion, as well as the added issue of having to search multiple potential venues for relevant research.

I understand that for research outside of your specialist area, a stamp of approval of some sort makes things easier, and more reliable. So while I don’t know how common cases like this will be, this is why I popped “Exercise judgement when it comes to publishing, citing, and re-using preprints.” in bold in summary section. For researchers on a personal level, this is what I would expect – the very fact that you’re saying you need a stamp of approval is you exercising your own judgment in this matter, and therefore is something I completely support.

I don’t think that’s shoddy scholarship either. However, if you only spend 20-30 minutes on papers core to your research, you might want to dedicate some more time to them! I know at least during my PhD, I identified 15-20 papers that were essential reading and made sure I understood them as well as possible, some times even taking a whole day to digest them fully! We all operate at different speeds and levels, but I think with at least the core literature, that sort of thoroughness is expected. For I guess what we might call ‘secondarily relevant’ literature, I mostly agree, except that reading should still be done critically and therefore is a form of review, just perhaps not as intense.

And yep, your final statement again I can support – you’re using your own judgment and experience to come to a conclusion that makes sense in your own context. Just as a follow up, what if it were a preprint that had been commented on to some degree by experts in the field? Would there be a threshold there of the detail/number of comments that would meet a threshold of ‘approval’?

Cheers!

Jon

p.s. Totally stealing your snake analogy for future discussions on this 😉

Yes, certainly a key text would need a lot longer than 20-30 min. Last year I tracked my reading and I read a little over 150 papers in one form or another. Often I’d identified them as part of one systematic lit review or another, and my objective was to establish which broad areas they had looked at, or how they’d used X method. In which case I can achieve my objective in a short time. Likewise if I get a journal alert I may skim read in 20-30min as a first pass, particularly if it is more of a tangential interest area – my objective is to parse the general info and methods and store it in my ‘mind palace’ (!) for when/if I need to come back to it.

I read around 30-40 papers last year completely in depth, so to the level a reviewer probably had, mostly (but not exclusively), in areas cogent to my specialisms. For those it varied, but I guess a couple of hours at least, many I return to time and again as if they’re well thumbed and loved paperback novels.

I wonder if there’s a way of systematically documenting literature ‘reviews’ and reading styles etc. like this in a way that might be useful in helping to document the research process..

Seeing as that’s fairly inflammatory, can I ask you to either justify your comments or delete them please, Jack.

this is basically my feeling too! Basically, I would only cite a preprint if I feel qualified to review that preprint. I am interdisciplinary (computational biomedicine). I will, for example cite a mouse genetics paper in the discussion of my paper, and I don’t know enough about mice or western blots to really evaluate it as a peer myself. So although I try to read it with a critical eye, I do rely on peer review.. But if it was a relevant preprint I really dug into all the supplementary methods on, I don’t see why I need to wait for the reviews to finish, as long as it’s clearly cited as a preprint, as Jon says.

Shouldn’t the sentence “The inverse is also true in this case, that just because a paper has not gone through traditional peer review, does not necessarily mean it has higher standards and is 100% true.”

contain one less negation? I think you are saying just because a paper HAS gone through PR does not imply 100% correctness. A simple proof by negation of “PR => high quality” is the existence of RetractionWatch, so I completely agree with your sentiment.

Secondly, I worry that preprint “culture” risks disadvantaging people with low connectedness on their discipline’s social network. At least with a journal submission/acceptance, there is some imprimatur of quality and a signal to the community that the work is worth reading (and you’ve “forced” 2-3 peers to read it). In my mind a far bigger risk from preprints is that no one reads it or knows about it. What if Ramanujan had simply posted his proofs on ArXiv instead of writing letters to influential British mathematicians?

Hi Neil,

Yes, you’re right – editorial oversight on my behalf, thanks!

And that is a good point. One of the things I keep reiterating is that while no system is perfect, we have to make sure that any we develop in the future are less risky/harmful to those who are already marginalised by current processes. This is one reason I think having preprint servers acting as community spaces of sorts is very valuable.

Cheers,

Jon

I treat preprints the same way I treat published abstracts, unpublished (but available) dissertations, etc. They’re not ideal citable objects, but if they’re all you have, it’s rude at best and potentially unethical* at worst _not_ to cite them. I include citations to acknowledge others’ work. Of course a final, peer-reviewed publication is best. But if a dissertation or abstract or preprint is all I have to cite, just out of fairness to my colleagues I’m going to cite those. I would expect the same out of them.

Example from a paper I published a few years back…we found an element of a rare organism in our museum collection. No examples of this taxon had been formally described from that area, that clade is generally rarely preserved, and it was worth getting our critter into the literature. However, a bit of research found an abstract mentioning another specimen from the same formation that had been published around 10 years prior, but no subsequent paper. I contacted that author as a courtesy (if their paper was just around the corner, I was happy to delay our publication), didn’t get much of a response, and made the decision to proceed with our publication. We cited that previous abstract, because (as outlined above) it would have been rude at best and misconduct at worst to ignore it and imply that our discovery was the very first. This situation is exactly parallel to citing a preprint–I see little harm and potentially great benefit in terms of collegial goodwill and my ability to sleep at night.

And on the authorial side, I completely understand that others might be working on stuff related to my own work, and I’m (generally) OK with that. Quite frankly, though, I would be somewhat annoyed and hurt if they obviously knew about my work via abstracts or preprints and chose not to cite that. Although I’m secure enough in my career, I see where students and early career people could be disproportionately affected by refusal to acknowledge or cite preprints.

Finally, I think the concern that the literature will suddenly be littered with references to preprints is a bit overblown. Thinking through the papers I’ve read recently, at most they’ll have a single personal communication, or a single dissertation reference, or whatever. Even in disciplines that have wide use of preprints (and notably also have a heavy concentration of “alternative research” from misguided yet persistent amateurs), this hasn’t become an issue. I picked three papers at random from a major astrophysics journal. One had 44 references, with only one for an arXiv preprint. One had 35 references with 5 arXiv preprints cited–one of those was already in press so the arXiv preprint was for the convenience of readers, one was in review, and all were dated to 2016 or 2017. The final had 49 references, with no citations of arXiv preprints.

[*because I used the word “unethical”, I should also clarify that if you don’t like preprints, no I’m not accusing you of misconduct. I’m just stating that for a small fraction of unethical researchers (probably not you who are reading this, don’t worry), “convenient” omission of acknowledgment of abstracts, dissertations, preprints, etc. can fall into the unethical category]

Hey Andy,

Thanks for this comment, very useful stories. I think, as Simon exemplified too in his comment, that you basically conform to my main summary point: “Exercise judgement when it comes to publishing, citing, and re-using preprints.” There will always be many different stories, contexts, and variables that factor into these things. As I mention a lot through the post, it’s our responsibility as scholars to get this right as a natural part of our jobs.

Regarding your final point, look at the Google Scholar metrics for the different arXiv subsections if you haven’t already – those things are cited more than the ‘top’ journals in the field! Seeing as physics hasn’t exploded yet, this seems like good evidence for no limited/no ill consequences of preprint citation, in this case at least.

Cheers!

Jon

Yes, as a physicist I can confirm and do fully support the latter observation and comment of Jon.

As a physicist who has used the (apparently most prominent and largest pre-print server) arXiv for almost a decade before becoming a publisher, I have a completely different view in comparison to Matt: He says in his comment above that pre-prints ‘are a neat way to get additional feedback on a manuscript before or during the traditional peer review process.’

I cannot recall a situation when anyone of us or any other group in my field posted their work as pre-print with this motivation. At complete variance, we and they made sure that the posted version was basically that last version which had been submitted in parallel to a peer-reviewed physics journal, eg PRL, PRA or PRB. Obviously, it was neither our, nor our colleagues’ intention to get substational feedback (which could have been and was easily achieved by private communication between our peers in advance) at this stage.

The only motivation to post a manuscript on the arXiv was the chance to make our work *immediately* and *openly* available to peers.

Most of my colleagues which continued their career in academia are meanwhile head of an institution or full professor in their field. From their feedback and the discussions with junior researchers in their groups, I know that the latter motivation is still valid. Therefore, I disagree – and not because of a personal opinion – with Matt’s conclusion that pre-prints ‘should thus not be viewed as anything but preliminary documents’.

Having said this, I wonder, when academia will recognize that pre-prints which are hosted on local servers (after a preliminary check to ensure formal scientific standards), could become the standard basis for a peer-review process organized and maintained by the scholarly community itself. This vison is not only my professional view as researcher and academic publishers for two decades, but was also discussed extensively in a blog thread by UK scientist Timothy Gowers in 2011f. It’s therefore a likely way of future scholarly communication and one may wonder today, why it hasn’t been discussed and established (much) earlier, at least in those disciplines, where pre-print servers existed for a longer period of time, as for exampld in physics, math computational sciences, economics, statistics,….?

Thanks for this great post! I have several comments. Personal preference I guess, but for me, I think they should be cited. In a way I think it’s no different than a conference poster for example. The peer review issue bothered me at some point as well. Not saying we don’t need it b/c I think peer review can improve a paper. But whether or not something is peer reviewed doesn’t make it good science. Some reviewers are better (i.e. more helpful) than others. Some may be very thorough, some may not. I think if the science is good and you believe it, you should cite it no matter what format. A preprint with solid data is better than a high impact factor paper which may end up getting retracted in spite of peer review. I think ultimately we should focus more on producing and citing good science (and reading the papers we cite) than the format.

Hi Adriana,

This is super interesting, thanks for the comments. I entirely agree with your final point on focusing on producing and citing good science, and also on how we can improve this process for everyone too.

Cheers!

Jon

Great discussion!

I think overall this conversation is pointing to a much larger issue that needs to be addressed – the current way research is shared doesn’t benefit science. The purpose of preprints is to speed up research dissemination. Citing a preprint would mean that you are pointing to the most current research you know of (while also citing a foundation of research examples). The traditional system is too slow to currently support this. I see this every day in my work as I help our grantees publish their research outputs. I’ve seen manuscripts sit in the queue for months waiting for peer review. Or a paper will be rejected before peer review and be submitted to another journal. Eventually, this manuscript will be published and considered “good” science, but it just didn’t meet a certain threshold according to the first publisher. And this threshold is often arbitrary (in my opinion) and varies per journal. I do believe that there is value in peer-review, but not in its current structure. And I do agree with many sentiments I’ve seen previously that it’s up to to the individual scientist or the larger scientific community to be able to spot “bad” science or a “bad” paper. Peer-review isn’t magical or fail proof.

I support trying different solutions to speed up research dissemination and evaluation. I think open peer review has great potential.

Hi Ashley,

Thanks for your input here, much appreciated. I’m biased, but agree that there is much that can be improved in the current system, and you pick up on many of these. I think one thing is beginning to stand out a little here: We need to inject some science into the way we communicate science!

Jon

Yes! This is a critical point. More studies into what works/what doesn’t would be extremely helpful. As an information professional I find this really exciting. Now if I could get funding/support for such studies….

I especially liked the paragraph highlighting the responsibility of the citation lies with the citer, because this responsibility is clearly being passed on to others.

If I write a paper, I read the articles I am about to cite, preprint or no, to be sure that a) I am citing them in a correct context and b) that I am happy that they are done to my own personal peer review standard and are worth citing. But, as many point out, what if I’m not an expert in that area? Well, before I publish the paper or archive the preprint, I send it around to colleagues, who do have that expertise, to have them check that what I have said and cited is correct. Honestly, if I’m writing about something that I don’t know that much about, then it seems highly unlikely that I will be writing it alone, but rather will have someone co-author it with me, as they likely have worked with me collaboratively on the project. But I take seriously the responsibility to cite things appropriately, because to me that is part of what defines my training and value as a scholar.

When I read papers, and see people cite things incorrectly, or cite crap because it happens to agree with them (which is the ‘fake news’ phenomenon being played out in science) it can immediately affect my judgement of the paper, and how I will cite it, or whether I cite it at all, as well as of the author(s), their other work, etc. The corresponding author has a responsibility to ensure all the citations, as well as the data and interpretations, are as correct as they can ascertain them to be, and my judgement of someone as a scholar is affected by their ability to carry out their duty in this regard, and I expect the same judgement of my own work by peers too. I realize that it may not always be perfect, but it can certainly suggest sloppiness whether I do it or I’m reading someone else’s work and they do it.

In addition, you can cite a preprint, or a paper, to point out that you disagree with it, or think it an incorrect study. Citation does not mean it is correct. Citation means you think it worthy to reference to support a particular argument you are making, or piece of evidence that someone else has provided in the context of your research. Citation measures importance. It does not establish validity. These concepts appear to be conflated in many of these discussions*. The infamous STAP papers, now retracted, are highly important (many cited them in a discussion of this issue like I referenced them right now) but invalid. My papers on why ubiquitin is added on weird amino acid residues on certain proteins in frog extract are (I hope! So far they hold up!) valid, but likely, in the grand scheme of things, not important**.

Giving responsibility over what you cite in an area you feel unable to evaluate to people you do not know is not a suitable reason to argue for citing peer-reviewed articles over preprints, in my opinion. Ask a scholar in that field whom you know/trust/should be collaborating with if you’re not an expert in the area you are writing about to check your writing on that field or work. I trust people I know and whose judgement I respect more than people I do not know. That is not a reflection on the peer review process, that is basically functioning as a human being. And I would go through the same process for a preprint or a peer-reviewed article. Jon is right, I would probably read the preprint more closely, but I’m not going to wait 2 years to write my paper to cite it or see whether it should be cited, when it finally gets published. Again, people who actually read my papers can evaluate my value as a scholar based on how I cite it.

*As an aside, validity vs importance is part of the discussion in a preprint I coauthored, here: http://sjscience.org/article?id=580.

**I will note that this is the reason NIH is shifting to use of the Relative Citation Ration, rather than just using citations like people do with the h-index; these papers may be cited by those who find them important, but usually in the small fields that are interested in non-canonical ubiquitylation or Xenopus biochemistry.

Hi Gary,

Thanks for taking the time to comment. I think you nailed it here: ” I take seriously the responsibility to cite things appropriately, because to me that is part of what defines my training and value as a scholar.” – what we need to make sure then, is that all scholars have the training and values to be able to meet this standard.

Also, this comment ” Citation measures importance. It does not establish validity.” I think is spot on. I mentioned that peer review was an important part of this, and I suspect that there is a strong correlation between faith in the current peer review system and lack of support for citing preprints. In fact, everyone who has been ‘negative’ in these discussions so far with me fits this exact profile. But n = small. Great comment, I think you got across some really key points here.

Cheers!

Jon

Assuming one can be considered a “peer” of the authors, citing *is* peer review.

What we perhaps need is machine-readable CONTEXT of citation. A way to differentiate “I endorse this” or “This is wrong” or “This may be worth considering” etc, and analyse that in scale. No idea how to get there with present tools, though semantic natural language processing (Meta, Iris) is developing really fast (some call those algorithms AI, but I refuse to call special-purpose scripts intelligent).

Then, peer review of a paper, or rather any scholarly object (btw, can we stop talking in terms of dead-tree technology someday soon?), could be a living thing from day one, instead of a way to assign a mineralised fossil “version of record”. Indices could be devised to get continuous rather than binary (or worse, prestige-based) assignment of scholarly credibility to an object – i.e. an endorsement that is itself repeatedly endorsed weighs more than a repudiation that is itself repeatedly repudiated.

But this means we need to accept that the scholarly value of a new object is simply UNKNOWN, before you or some peer actually, you know, read it. And even after a few citations, we are still profoundly UNCERTAIN of said value. Which should be fine, as we are *researchers* and thus uncertainty is our bread and butter.

Although, arguably an “unpublished” object with just four endorsing citations is more trustworthy than a new paper in Nature/Science/Cell – because it has been approved by at least one more peers. Though the word “unpublished” is bit of an oxymoron for a thing that has been cited, no?

Hey Janne,

Thanks for posting the comment here, some super interesting stuff. One quick thing – there are different forms of peer review, and I think it’s important to make a distinction between the type of evaluation that citation implies, and what people regard as traditional peer review.

Absolutely agree about the context of citations. Another infuriating thing about scholarly publishing is the almost total lack of hyperlinked references. When I see a citation in a text, why can’t I click on that and go to the exact bit of text/image/whatever in a paper and see what it is referring too. The internet enables this entirely, yet we don’t have it and it’s daft why not. Combine that with your context engine, and then you’ll start to see deeper evaluation of citations, as well as inevitably their proper usage.

I think there is also some truth in what you say about the uncertainty of a peer reviewed record. We shouldn’t take things as peer review = correct, and accept that there are flaws in the system, and then consider more deeply what the implications of this are and then how to fix them. The term ‘published’ in academia is unique, as it means also that it has implicitly ‘passed’ peer review. So therefore while a preprint has been published, it is not considered to have been ‘published’ sensu stricto. So you have to rethink what publication truly means, how this is coupled with peer review, and then how you value the different parts of that. Anyway, great comment.

Jon

p.s. Hat tip for making a reference to fossils too – you know how to appeal to me 😉

Thanks Jon, for writing this up and give more reasons for us on why we should consider preprints in our citation list.

I read your long post and couldn’t agree more. I am working in an “old-fashioned” environment, which still very much attached to traditional peer review. Indon’t argue with that, but at the sam time, they are also very iritated with the long duration of peer review. As you know, English is not our first language. So they would spent 6 months alone only to setup the language and another 6 months to respond to reviewer’s comment, which is still encircling in language problems. My PhD paper took me 2 years before it got formally published.

So writing papers and get them out as preprints would be a great opportunity for us to learn and to get more out of our system as quickly as we can, given all docs should have a proper presentation of data and analysis. We could make a model about the language part, for example: a full Indonesian language text with extended abstract in English, or accompanying slides in English.

Therefore if more people cite preprints, then there’s a slightly chance that our “English language” papers could be read and eventually cited by others, given the situation that the readers can always send an email or another kinds of communication directly to the authors to clarify the unclear parts.

I’m sorry if you find this respond is not directly related with your original post.

Hey Dasapta,

Always have time and appreciation for your input! I think it’s very important that we consider the potential value of preprints to all researchers, which includes the non-native English speaking community. If you think preprints are a way to help accelerate scholarship in countries like Indonesia, then you have my full support behind you and I’ll do what I can to assist!

Cheers,

Jon

I actually think this is a non-issue – I don’t see any difference between citing pre-prints, and citing conference abstracts, unpublished theses/dissertations or personal communications. They all, in one way or another, acknowledge and credit a previous piece of work, expertise or opinion. If a pre-print (or abstract or thesis) were the only piece of work introducing an idea you want to expand or discuss in your own manuscript, and you knew about its presence or have read that piece of work, then I think it would be disingenuous not to cite it – like Andy’s commented already above.

I think blindly favouring peer-review over preprints is in itself a foolish, if not dangerous act – I’ve seen too many peer-reviewed published articles that have serious fundamental flaws that I’m appalled none of the reviewers or the editors picked them up. I suspect in those cases neither the editors or the reviewers were actually appropriate (to review the specific methods employed in the manuscript) that they thought it was all right. So, in such circumstances (which is going to be increasingly more common as more and more sophisticated methods become available to non-methods researchers), open review (of archived preprints) is probably better since the appropriate reviewer can make the proper comments.

In that vein, I’ve only cited two pre-prints (both on bioRxiv), which were on subjects that I have some level of expertise on (and colleagues with more experience and expertise on the subject have vouched for them). I’m not sure if I will be citing preprints on subjects I am not very familiar with. I suspect that would be generally the case with most researchers who are considering citing preprints (I may be wrong of course)?

Hey Manabu,

I’ll address all 3 of your comments here as one 😉

For a bit of context, Manabu is from the same field as myself and probably many other readers here (Dinosaurs), and writes excellent papers like this: http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/2041-210X.12666/abstract that help to basically undermine quite a bit of recently published ‘high impact’ research by pointing out severe methodological flaws. See also this paper: http://palaeo-electronica.org/content/2015/1357-residual-diversity-simulation [Sidenote: While we’re here, Manabu, you can totally upload a preprint of your MEE paper and a postprint in a few months – it’s paywalled atm and Unpaywall couldn’t find a ‘green’ version 🙂 ]

“I think blindly favouring peer-review over preprints is in itself a foolish, if not dangerous act” – I think there is some truth to that, and we should accept our responsbility as peers to do this rather than exclusively pass that on to an anonymous process. But also, as I’ve said a few times, informal preprint evaluation is a compliment, not a replacement, for formal peer review. No one who stands by this can possibly believe Matt’s accusation “If you cite a preprint, you are more or less saying that you do not value peer review.”, and as far as I’m aware, no one has called for a total replacement of the traditional system.

And your last comments are just you exercising your professional judgment, and as we’ve seen from other commenters, is totally okay. “Exercise judgement when it comes to publishing, citing, and re-using preprints.” There’s a reason why I put this one in bold.

Cheers!

Jon

Hi Jon,

Thanks for linking to my papers! With regards to our MEE paper, the University of Reading should have a “preprint” version of our MEE paper archived, but I don’t know how accessible it is from outside if Unpaywall couldn’t find it – I’ll chase this up.

I’m also not advocating for a replacement of formal peer-review, just pointing out that just because a paper’s been reviewed doesn’t mean that it’s fail-proof (I guess that would naturally lead to post-publication peer-review?).

And totally fine with what you said about exercising professional judgement – I was kind of trying to get at something like that but I guess it didn’t come across very well..

No worries – maybe Unpaywall just doesn’t crawl that particular repo 🙂

And re. the last couple of points, pretty sure we agree on most aspects here 🙂

Oh, I forgot to add…There was a tweet by Matthew Shawkey that initially caught my eye, which led me to this whole thread on Twitter:

My previous comment can be construed as a response to this…

…that is, traditional peer-review isn’t perfect to begin with, and citing preprints doesn’t mean you’re circumventing peer-review (sorry, I keep adding comments…)

I started reading this on the fence and I am still somewhat on the fence I think. Both arguments have parts that seem valid and both have parts with logic I struggle to follow too. A few below…

– Jon, It seems to me that the logical conclusion of “Evaluating papers is basically a form of peer review, therefore a citation is a sign that we have critically reviewed a paper and decided its value; or at least it should be” is that we may as well do away with formal peer review. Maybe we should? But then you also skip to saying that comments on preprints are a form of peer review. Which kind of muddies the waters since but you just said authors should peer review the papers they cite themselves, in which case who cares about the comments?

– On the other hand Matt (and Jon), do people really use preprints as a way of getting feedback? I thought they were really mainly used as defacto open access and a precedence step for papers that were accepted. In which case preprints do = standard article. After reading the debate between you two I suspected I had the wrong idea on that and that maybe this was the case only in my small area of research, however the comment above suggests it is also the case in physics (and a recent post and comments on dynamic ecology blog suggests the case there also).

As an aside how many people really comment on preprints anyway. And do the authors of preprints really expect that (I will try and dig up that Dynamic Ecology post with comments as from memory they came to the conclusion that authors dont expect or even want comments)? The whole comments thing seems like a bit of distraction to the main argument in my mind. And if it turns out that for a given field preprints are just an OA/precedence measure then the whole debate above becomes almost pointless for that field surely?

After all that I think I am in the perhaps logically indefensible position of planning on citing preprints but as a last resort for example when a) they are an OA version of an accepted article that I want to cite before journal gets around to getting the article online, b) that is all there is available and therefore I will “treat preprints the same way I treat published abstracts, unpublished (but available) dissertations, etc. They’re not ideal citable objects, but if they’re all you have, it’s rude at best and potentially unethical* at worst _not_ to cite them”.

Hi Vladimir, thanks for these comments. Lemme try and address them in turn (my hands are aching a bit now after all this!)

1. I don’t think we should do away with formal peer review, which is why I wrote the brief section on it “Issue: Citing preprints under-values formal peer review. While there are always exceptions, peer review generally benefits both authors and articles. By citing a preprint, you are not de-valuing this process. You are simply using your own judgement, while an article is undergoing formal peer review, to decide whether or not to cite an article and the context of that citation. They are not in conflict, they are complimentary.” That’s not to say there aren’t improvements that I think can be made, as I’ve written about elsewhere (eg http://blog.scienceopen.com/2017/04/a-new-gold-standard-of-peer-review-is-needed/). It’s important to note that there are many different forms and flavours of peer evaluation, that form a complex network or continuum.

2. While some people might use preprints as a way to gain feedback, I mentioned in the beginning that the main reason for preprints is that “They are intended to get the results of research acknowledged and make them rapidly available to others in preliminary form to stimulate discussion and suggestions for revision before/during peer review and publication.”, and therefore this forms just one of the key advantages of preprints. If no one comments on a paper, nothing is still lost, because it’s a complimentary process to formal peer review and publication.

3. One of the most up to date overviews of ‘post-publication commenting’ systems can be found here, and is well worth reading https://scholarlykitchen.sspnet.org/2017/04/27/stop-commenting-already/ So yes, if the single intention of preprints is rapid dissemination, then using the feedback-based argument is a straw man. If there is the dual advantage of rapid dissemination and feedback, then this is perhaps less of an issue.

4. Your position here again seems fine to be. Trust your judgment as a scholar to make the best decisions for you and your community. 🙂

Hope that helps a bit.

Jon

Thanks for the reply. Seems you have both touched on a point of much interest.

1. Fair points all but never the less the caveats you add don’t really convince me that isn’t the logical conclusion of all this. Especially as you make a point of individuals being able to peer review a paper as effectively as a a number of reviewers. If self reviewing a paper is that effective then yes peer review is not needed.

I guess that is the main point I like of Matts; I do think that 3 other researchers reading a paper are generally more like to find a flaw than me alone…on the other hand on a paper on an area I was an expert on Id still evaluate the paper and cite it, I just would not be as confident in it as a paper that had min 2 reviewers plus editor plus me ‘reviewing’ it. I guess I’d also say I am immediately a little wary of someone that is 100% certain that their review of a paper is equal to this review process. Of course it might be in some cases but still that feeling remains.

2. That is the thing though, I’ve never seen a preprint used as a preliminary form of a paper. Though on that its hard to see beyond my own field so Ill accept that argument. On the comments part, I agree also that if no one comments nothing is lost but I don’t think you can use them as a plus on the side of preprints since they never happen.

3. I have read the scholarly kitchen post before and it is interesting but mostly confirms my view that comments rarely happen.

4. I think it may change a little still. Some of the arguments on here are already making me reevaluate exactly why I think what I do.

Thanks again. Ill keep an eye on the discussion.

Ps: “Another infuriating thing about scholarly publishing is the almost total lack of hyperlinked references”…drives me nuts.

Hi Vladimir,

Bear with, it’s 2AM now here and I’m getting weary after doing this all day 😉

1. In terms of peer review, I stand by my points that citation of preprints does not do away with the need for the traditional process, in some form or another. I personally do not think that any one form of peer review is ever enough, as we don’t have any way of assessing the integrity of the process at all. What we shouldn’t do though, as has been mentioned before, is make comparisons based on arbitrary, closed, and secretive processes (see eg here for more thoughts on this issue http://blog.scienceopen.com/2017/04/a-new-gold-standard-of-peer-review-is-needed/)

As you mention, expertise comes in handy here. Because that’s what judgment is largely based upon. This is again why it’s up to individual researchers/teams to take the time and responsibility to carefully evaluate before diving in without thinking. Making all review reports and decisions transparent would be awesome in allowing others to evaluate the relative quality of different types of peer review process across fields.

2 and 3. These sorts of things take time to become adopted by research cultures. As we see more preprints, more opening up of peer review itself, we should see more interaction with preprints. Of course, this might also involve some sort of incentive structure change too.

4. All for the better, I hope, As I’ve tried to carefully respond to each comment here and present a decent overview, I’d like to think this challenge has made me a better and more informed person in this debate thanks to you all.

Thanks to you too. I’m going to pass out now. Have an awesome week!

Jon

p.s. Word.

Hi thanks for starting this conversation. I think also we need to look beyond researchers, and consider how preprints might be cited/understood/perceived on Wikipedia, for example, and (a broader question) how the preprint concept (causing enough debate within research community) might be viewed by non-researchers who work politically and socially to push for evidence-based policy, with a focus on ‘peer reviewed literature’. And that placard seen at recent protest events – “What do we want? Evidence based science! When do we want it? After peer review” – isn’t easily improved as a message by adding clarifications regarding flaws, delays, peer review models, preprint servers, institutional repositories….

Hi John,