Is Torosaurus Triceratops? The debate rages on!

This was originally posted at: http://blogs.egu.eu/palaeoblog/?p=1138

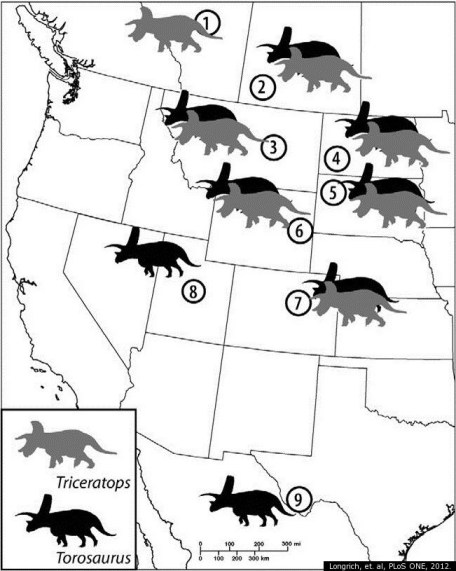

For some time now, there has been much debate about whether our beloved dinosaur, Triceratops, is a distinct species, or a younger version of a bigger ceratopsian, Torosaurus – the great Toroceratops’ debate. Proponents of both sides of the argument have made detailed quantitative and qualitative points, and there doesn’t really seem to have been any resolution. Check out the video below for a great discussion of the issues, or this link or this link.

Enter geometric morphometrics (GM). Everyones’ favourite-sounding method, GM is essentially a way of analysing the shape of objects, like fossils, using co-ordinate data. There are a range of statistical ways of spanking your data into shape once you have a digital version of it, and have converted an object into a series of point co-ordinates (decent-ish explanation in the methods section here).

What it is for scientists is a way of introducing statistical rigour to test a hypothesis. It’s really frickin’ useful, pretty much. The hypothesis which Maironi et al. wanted to test was whether Triceratops, Torosaurus, and Nedoceratops, another dino that might be just a younger Torosaurus, were distinct enough to not be regarded as a single growth series of the same species. Using geometric morphometrics, it is possible to visit the shape variation that specimens exhibit, as well as whether they truly represent discrete groups.

I didn’t want to this post to be critical of the methods for this paper, but they have missed a few essential steps. If you want to test for discrete clusters or groups within your data, principal components analysis (PCA) is not really the right method, as this study uses. PCA is a way of taking a high-dimensional data set, as you usually get using GM, and reducing it into fewer variables that represent a high proportion of the variance within that data set – usually, 95% of the variance is the accepted minimum required to be represented by a number of principal components.

In this case, 12 (!) PCs represented 95% of the variance in the reconstructed digital dinos. The first two only represent about 60% of the data – it is, then, entirely inappropriate to analyse just these two when they represent such a small proportion of the original data. What the study essentially does, is attempts to interpret distinctiveness of the different species, in a ‘morphospace’ that firstly isn’t designed to test for distinctiveness, but also fails to faithfully represent the data. Ideally, you’d want to analyse the dispersion pattern of all of the specimens with respect to the first 12 axes – this would tell you about the shape changes that are being represented by each axis.

The next step should have been to use a form off discriminant analysis – these tests are designed to test for group distinctiveness, as they incorporate group-level information as an additional variable; in this case, the species’ ID. Performing this would tell you how accurate, or distinct, your supposedly different groups are, and you can test the proportion of specimens that are correctly ‘assigned’ to each group. I go into this protocol in some detail in a forthcoming paper, and will discuss it more then. For now, I feel a bit bad saying, but this is really only half an analysis, and a lot more could have been and should have been done with it.

Nonetheless, there are some interesting results, if not based on an entirely substantial analysis (imo). Importantly, Torosaurus and Triceratops, in the context of the first two principal components, occupy different morphospaces, which suggests that they can be delimited based on shape as well as their sizes. That’s pretty much it. Another piece of the puzzle suggesting that we can keep Triceratops alive, for now!

Fortunately, the authors have been jolly decent uploaded their raw data, so I’m gonna go have a play with it and see what we get.. BRB

Reference:

Maiorini, L., Farke, A. A., Kotsakis, T. and Piras, P. (2013) Is Torosaurus Triceratops? Geometric morphometric evidence of Late Maastrichtian ceratopsid dinosaurs, PLOS ONE, 8(11), e81608 (OA link)

Ah, Open Access papers. If we didn’t have access to them, we’d have to watch football, or take up extreme body modification, or some other distraction.

Making me shiver at the very thought of not being able to science..

Science gives us reasons to science, like a perpetual science machine … of science. Why, the very thought of doing science makes me want to do science. Where’s an hypothesis I can test!?1