How to destroy generations of childhood memories in an instant: Yutyrannus huali

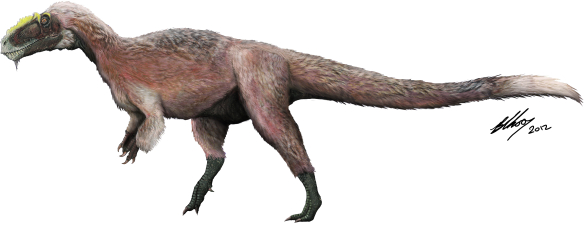

Childhood memories of dinosaurs have received another shattering blow today. The latest culprit is Yutyrannus huali, a large basal tyrannosauroid from the lower Cretaceous of China, complete with elongate integumental filament structures, or ‘protofeathers’. The etymology is quite special, says lead author Xing Xu, translating into a blend of Mandarin and Latin as ‘beautiful feathered tyrant’. This species is the latest wonder to be exhumed from the fossil treasure trove known as the Yixian Formation, a series of volcanogenic and lacustrine deposits that are currently guiding and re-working our understanding of dinosaur evolution. Of course, being such prominent study, Nature saw fit to pop it behind a $32 paywall.

Yutyrannus was pretty big for its geological age weighing in at around 1400kg, based on an estimate using femoral length (a standard proxy for dinosaurian body size estimates). As such, it represents the largest known dinosaur species to possess feather-like structures (‘protofeathers’, or elongate filaments), and is around 40 times larger than the previous contender, Beipiaosaurus. This gave it the appearance of a 1.4 tonne bird chick, with big teeth. Along with previous basal tyrannosauroids, such as Dilong, it appears early feather progenitors were pervasive among the group in the basal forms around the lower Cretaceous, irrespective of body size. Don’t be fooled by articles saying that these are “primitive” structures (*looks at the Daily Mail*) – they represent the beginning of a huge evolutionary step in bird-line archosaurs, one which ultimately led to the diversification of the most successful extant terrestrial vertebrate group, and represent an unparalleled leap forward in integumental morphology. Primitive is a relative term; they’re ‘primitive’ with respect to flight-enabling pennaceous feathers (‘true’ feathers), but ‘advanced’ with respect to scales. One could go as far as saying that tyrannosauroids represent an ‘adaptive radiation’ in the lower Cretaceous, based on their increasingly apparent disparate morphologies, and, along with contemporary sympatrics such as Sinotyrannus, gave them ecological dominance as apex predators at the time.

The filamentous structures are variably and sporadically distributed over the three known specimens and, assuming distribution is homogeneous within species (with preserved distribution a taphonomic artefact), can be reconstructed into a composite specimen with a near-complete coverage. Combined with their dense ultrastructure, this suggests that the bristles were used primarily for insulation, which is concordant with geochemical evidence showing that lower Cretaceous China was substantially colder than the rest of the planet at the time (e.g., Amiot et al., 2011). However, if they are patchy in distribution this suggests a possible alternative function, such as sexual display. The function of these structures, and the co-evolution of feather form and function is still hotly debated. One thing is certain, and that’s that Yutyrannus was not capable of powered flight or gliding. What they clearly demonstrate is that the initial evolutionary phases in feather construction were not designed for flight, and that flight, therefore, is an extrinsic by-product of a primary function. Xing mentions in the Nature podcast (see below) that samples have been taken for microstructural analysis to deduce the colour of Yutyrannus, following previous research on other feathered theropods (e.g., Li et al., 2012). This will guide future interpretations of exactly what early feather-like structures were used for.

Three specimens are currently known of Yutyrannus huali, plausibly representing an adult with two juveniles, based on overall size and morphometrics, purportedly occurring together (although the Supplementary Data seems to suggest the authors don’t even know which quarry they’re from!! *alarm bells*). If genuinely found together, this could be either construed as evidence for social behaviour, such as hunting, extensive parental care, or just be a chance occurrence with specimens washed together post-mortem. The three specimens show differences in their cranial morphology, in the context of gross dimensionality and relative structural position. Assuming that these are not artefacts of burial-induced deformation (as is persistent in almost all known dinosaurian skulls), the authors postulate these to be ontogenetic variations. If the three specimens were not so closely associated, this should instantly be a cause for concern to palaeontologists, and relates back to the question of rigorously defining species in the fossil record. Either way, it’s a pretty small sample size, so not really something that can be stated with confidence.

There has been a lot of [media] conjecture since this discovery, that perhaps now Tyrannosaurus rex itself possessed integumentary structures, but we’re just not finding them due to the taphonomic conditions of the rocks in which specimens are found. This is contradictory, as it cannot be speculated that protofeathers have a strict functional role, and then additionally that they in fact may have pervaded all tyrannosaur lineages as, what would implicitly be, a functionally redundant structure, given the entirely different conditions in which T. rex and cousins lived in the Late Cretaceous (an 8°C mean annual air temperature difference at the same latitude). It’s not quite as bad as, say, assuming all dinosaurs were aquatic, but it does undermine what palaeontologists are trying to understand with respect to feather evolution – the [beautiful] correspondence of form and function.

I won’t go into their phylogenetic analysis too much, but their open declaration of scoring juvenile specimens is a point of concern, especially as they have previously pointed at that allometric growth through their purported ontogenetic series is quite substantial. This is reflected in their specimen scorings, in which there are severe discrepancies between the three (if these weren’t assumed to be ontogenetic variants, would they have been classed as different species?). They perform two relatively mediocre cladistic analyses, the results of which are in the Supplementary Data. The lack of support measures used is another major point of concern (any systematist worth their salt would disregard any tree without at least bootstrap values), especially given their consistency index score of 0.27 for the whole theropod data set, suggesting homoplasy is running rife (an interesting point in itself). Either way, Yutyrannus appears to be well-resolved as a basal tyrannosauroid, although without any node/branch support values, this hypothesis is a bit shaky.

For the future, I guess we have to sit and wait to see what the fossil record churns out next. Further understanding of the interaction of the sequence of feather evolution and the physiological impacts is undoubtedly required, and something that I look forward to greatly. ‘Feathered’ sauropods and higher ornithischian taxa would be bizarre, but not unexpected now given that integumentary structures are widely scattered over the dinosaurian tree. Similar structures have been recovered in basal ornithischians previously, suggesting that some form of elongate integumental structure was symplesiomorphic for all Dinosauria. One thing is for sure though: the evolution of feathers is, without a doubt, the most significant step in vertebrate evolution since taking their first steps on to land.

Additional coverage:

Ed Yong at Not Exactly Rocket Science

Love in the Time of Chasmosaurs

References*:

Amiot et al. (2011) Oxygen isotopes of East Asian dinosaurs reveal exceptionally cold Early Cretaceous climates, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108, 5179-5183

Li et al. (2012) Reconstruction of Microraptor and the evolution of iridescent plumage, Science, 335, 1215-1219

Xu et al. (2012) A gigantic feathered dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of China, Nature, 484, 92-95

*These are all paywalled – I’ll be happy to send pdfs on request.

* one which ultimately led to the diversification of the most successful extant vertebrate group*

Well blow me. I didn’t know that tyrannosaurs evolved into teleosts?!

*terrestrial. And it’s with strict reference to feathers..

Although now for your next blog, you have to include a tyranno-fish

I have to say that I came into the Yutyrannus explosion a little later than I would have liked but, although it is quite clearly a sensational animal, I agree with you, Darren Naish and Andrea Cau (amongst others) that there are clear phylogentic concerns and question marks regarding this taxon.

I also have to say that I’m not very impressed regarding the provenance of the specimens either and it would not surprise me in the least if other “concerns” will raise their heads in the next few years as the specimens are more intensely studied and the full osteology becomes apparent.

Great post Jon!

I know nothing whatsoever about the systematics of tyrannosaur-grade taxa. I’m more concerned that Nature, and many other journals, are consistently letting half-arsed attempts at cladistic or phylogenetic analyses through. I mean, it’s not that difficult in theory or practice, and is a core part of Palaeontology!!

The default assumption should never be that they’re the same!! There is evidence to show that they are different, with respect to how they’ve scored the three specimens (see the Supplementary Data), as well as qualitatively in the main text, where variations are attributed to ontogenetic allometry.

147 species concepts..whew! Do you know how many of these concepts are applicable to fossil taxa?

The default assumption should always be that things are the same unless one can demonstrate an actual difference based on clearly defined criteria. Unless you want to entirely redefine the protocols of scientific investigation. Perhaps you should reconsider the methodologies you have used in the past and see for yourself.

On another hand, attributing variability to developmental causes is also one step short of acknowledging the fact that no two individual organisms are absolutely identical, even true twins, considering the effect of phenotypic plasticity.

As for the phylogenetic analysis: results are never better than the data and you have accurately pointed out already that it was gathered in a somewhat clumsy manner. The result of it is that the paper makes the news, gets discussed and thus gathers more attention from the general public and a broader panel of scientists than just dinogeeks. All in all, I think it is a very “successful” analysis, but not for scientific reasons, perhaps we should remember that and get training on writing errata as well as papers 😉