How did birds get their wings?

This was originally posted at: http://blogs.egu.eu/palaeoblog/?p=680

How many fingers do you have? Hopefully, 5. Do you think that’s the normal condition for all animals? Do you think that’s air you’re breathing right now? … OK, so I watched the Matrix last night, but still, do you think all tetrapods (dudes with 4 feet, including you, and anything else with four flippers, wings, or feet) have 5 digits on each limb? Actually, there’s a pattern within tetrapods of limb reduction in various lineages – our earliest ancestors seemed to experiment with digit numbers and went a bit berserk by growing extra fingers from their fishy flippers.

One of the most interesting, and therefore controversial-enough-to-be-used-against-palaeontologistss-by-whacko-creationists-and-anti-evolutionists-who-probably-still-live-in-the-attic-with-their-mothers, aspects of this whole menagerie of tetrapods trying to decide how is best to give the finger, is the transition from dinosaurs to birds. In case you hadn’t realised, this is quite an important evolutionary jump, as to go from something that doesn’t fly to something that does, you have to do something quite special to your body rather than gluing bits of plasterboard on to your arms and flapping real hard. Of course, this can work if you’ve had enough beer, but birds don’t drink. As such, they had to develop some pretty cool anatomical modifications to learn how to fly.

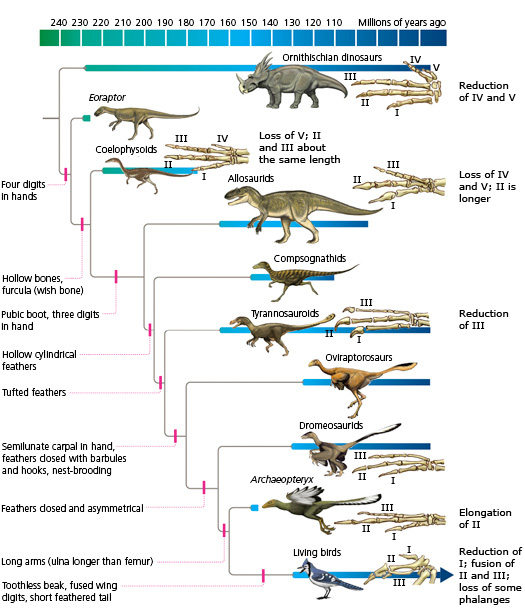

The dinosaurian ancestors of birds, the tetanuran theropods (the big ones who like eating lawyers, according to the latest scientific information), had three clawed digits designed for grasping prey. For a long time, these were considered to be anatomically identical to the three digits you get on modern birds and their avian-line ancestors. This is called homology, and is what palaeontologists use along with sophisticated programs to determine the evolutionary relationships of organisms. In birds and dinosaurs, it wasn’t this simple though. It never is.

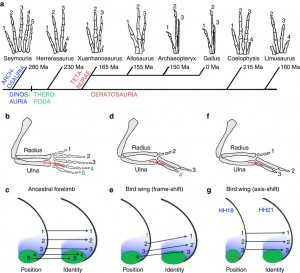

Scientists are superbly anal. This goes far enough that they actually put numbers on almost everything they can. This includes fingers, and for once, actually came in useful. It turns out, that if you look at the anatomical similarities between the digits of birds and dinosaurs, something odd happens. Dinosaurs have what are known as digits I, II and III of a ‘perfect’ 5-digit hand (known as the Lateral Reduction Theory (LDR)). Birds, on the other hand (ha. ha.) have a formula of II, III, and IV (written as II-III-IV, known as the Bilateral Digit Reduction theory (BDR)), based on their individual anatomies and through looking at how they develop in the embryonic stage. The battle to reconcile this pattern, or refute the entire theory of evolution based on it, has lasted for slightly longer than it takes to push forward a sensible bill through supreme courts (about 200 years). The transitional theory is known as the ‘homeotic frame shift’, which is only worth including here as it sounds awesome, identified by the way in which certain bird genes express themselves during embryology.

In dinosaurs, you can track a reduction of digits IV and V through time. This is different to many other tetrapod lineages, where you can track the gradual loss of I and V, such as in turtles. So if you consider just the pretty fossils, then really there’s no problem. Birds match the dinosaurs toe for toe. Yeah, these crap puns aren’t going anywhere. There are some dinosaurs that break this rule though. Limusaurus is a minisaurus from the Late Jurassic of China (about 140 million years ago), and has a reduced digit I, which means it follows the bird version of BDR. Some early tetanurans also have the bird-like II-III-IV formula, so what is going on?

What this tells us to begin with, is that to get a proper killer story about evolution, you have to combine the fossil record with developmental biology, embryology, and just every other cool branch of science out there to understand properly.

Genes are cool. One in particular, known as sonic hedgehog, is a gene that expresses itself in cells and acts to control the development of digits, particularly that of the pinky, or digit V. You can use the expression of these genes to determine the difference between different digits that look the same morphologically, but are actually different structures – this happens quite a bit in biology, for example with cryptic species, or those which look identical but are actually totally different organisms! In mice, you can actually fiddle with the sonic hedgehog gene, and change their developments to lose various digits during growth, including the middle ones.

Another way of looking at these developmental patterns is at the bone itself. Bone begins growth as a condensation of pre-cartilage cells along the limb axis. Digit IV is typically the first to begin life in tetrapods, and therefore can act as a reference point for when the others start to pop up and give an idea as to which digit is which. Oddly, what analysis of this suggests is that birds have a I-II-III identity, completely different to that known from morphological and genetic data!

In mice again, digit III is the last condensation to form. According to Moore’s Law of developmental biology (specifically of evolutionary loss of structures), the last element to form during embryonic growth is the first to be lost in an evolutionary trajectory. If this were the case, it could imply that tetanurans actually have a I-II-IV pattern. If this were the case, it would go some way to aligning the apparently different bird and dinosaur signals.

So as it stands, there isn’t really a consensus at the present. Superficially, birds look like they have the II-III-IV patterns, but developmental and genetic data actually suggests this is more likely to be I-II-III. Tetanurans are considered to have II-III-IV or I-II-III, depending on how you interpret what it is birds have and under the criteria of parsimony (the solution with the fewest ‘steps’ is the most likely). What is needed in the future is a re-examination of the tetanuran fossil record in the light of new genetic and developmental data, and of course, more fossils!

Further reading:

http://www.nature.com/ncomms/journal/v2/n8/full/ncomms1437.html

http://www.cell.com/current-biology/abstract/S0960-9822(13)00512-5