Dining with a starfish

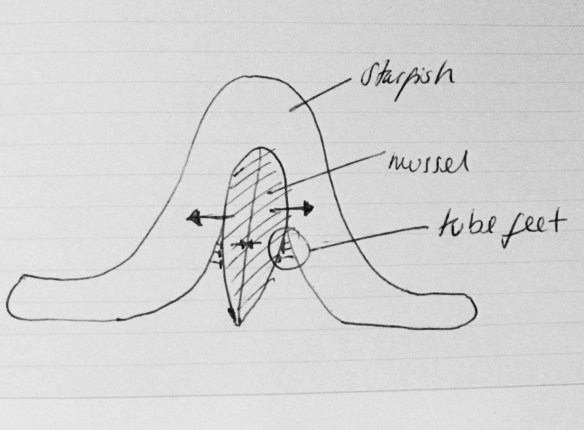

There’s nothing quite like seeing something in the field. I came to this realisation about half way through my Masters course. When I started, I was a fully-fledged Geoscientist and taking on biological knowledge would have been an immense challenge if it hadn’t been for the engaging, rapid-fire seminars given by Dr Rob Hughes. He was responsible for the series of lectures dubbed the ‘rampage through the phyla’ – a crash course in invertebrate taxonomy, morphology and ecology. Many a lecture was spent sketching the characteristics of a particular family with the urgency of a Pictionary player under pressure, which is how this came about:

Starfish, or Asteroidiae, to you and I, have an abundance of fantastic appendages known as tube feet. These are highly flexible structures that can move independently of one another, each ending in a sucker-like pad. Not all the tube feet need to be employed at the same time for a starfish to gain purchase, allowing it to grip onto surfaces for extended periods without wearing out. This gives them a huge advantage when preying on other invertebrates…

They are formidable predators, enveloping their prey and using their tube feet to pull it apart. This is a long process, but the ability to alternate between tube feet means that they tire far slower than their prey. Mussels, for example, have only one muscle to keep their shell closed and it soon weakens from the strain of resisting a starfish. Eventually, their muscle gives way and their shell opens, defeated. Starfish begin digestion externally, everting their stomach to cover their prey and secrete digestive enzymes that break it down for resorption into their body. This means they can take on much larger prey than their mouths would otherwise be able to handle – sea urchins, for example.

Sea urchins (Echinoidea) are also in possession of these fantastically sticky tube feet. When threatened they are capable of disengaging from their rocky holdfast and tumbling to a safer spot further down slope. The caveat: what if they aren’t on a rocky slope? Well, such an escape mechanism is of no use when sitting on soft, even sediment and you’re faced with a determined predator. While diving off Greater Cumbrae I encountered an urchin whose unfortunate position in the silty shallows led it to a miserable fate…

Murky, sediment-laden waters gave way to a monstrous, spiny starfish – Marthasterias glacialis if you will – arched high over a now spineless, lifeless, urchin. Motioning enthusiastically to my dive buddy I edged closer, enthralled. No longer the subject of a poorly scribbled lecture note, but the real thing, gluttonous and threatening and wonderful. Perfectly poised, the starfish was just pulling away from its latest victim. Its stomach, now fully satisfied, had already been returned to its inter-meal home within the body cavity and a creamy plume of digestive juices drifted down current. Tasty. I looked back at my buddy keenly – isn’t this amazing?! But there was no buddy to be seen – I was so enraptured by the spectacle that I has completely lost sight of her.

A few metres above me, and struggling with her dry suit, there she was. I left the scene – reluctantly, I confess – to make sure she was okay. She was. By then though, it was time to move on and I had to leave the magnificent spectacle behind me. There’s a special kind of understanding that comes from seeing something in the field and it certainly beats a quick lecture sketch. Get out there!

Ah, the joys of seeing it in real life.

As a mantle petrologist and igneous petrogenesis-ist by training, I tried ploughing my way through Lynn Margulis’ (and A.N.Other) “Five Kingdoms” as a “rampage through the phyla, making notes as I went on.

I got as far as phylum 40-odd, in the Animal Kingdom, before conceding defeat when I noticed that the second edition was out, revising about a half-dozen phyla. Will someone please nail the squishy things down!