11. Peer Review: Anonymity Versus Identification

This is adapted from our recent paper in F1000 Research, entitled “A multi-disciplinary perspective on emergent and future innovations in peer review.” Due to its rather monstrous length, I’ll be posting chunks of the text here in sequence over the next few weeks to help disseminate it in more easily digestible bites. Enjoy!

This section describes the lively debate around whether peer review reports should be anonymised or not. This is a big topic, so I’ll slice it into a few smaller posts to make it easier to read. Previous sections:

- An Introduction.

- An Early History

- The Modern Revolution

- Recent Studies

- Modern Role and Purpose

- Criticisms of the Conventional System

- Modern Trends and Traits

- Development of Open Peer Review

- Giving Credit to Referees

- Publishing Review Reports

Eponymous versus anonymous peer review

There are different levels of bi-directional anonymity throughout the peer review process, including whether or not the referees know who the authors are but not vice versa (single blind; the most common (Ware, 2008)), or whether both parties remain anonymous to each other (double blind) (Table 1). Double blind review is based on the idea that peer evaluations should be impartial and based on the research, not ad hominem, but there has been considerable discussion over whether reviewer identities should remain anonymous (e.g., Baggs et al. (2008); Pontille & Torny (2014); Snodgrass (2007)) (Figure 3). Models such as triple-blind peer review even go a step further, where authors and their affiliations are reciprocally anonymous to the handling editor and the reviewers. This attempts to nullify the effects of one’s scientific reputation, institution, or location on the peer review process, and is employed at the open access journal Science Matters (sciencematters.io), launched in early 2016.

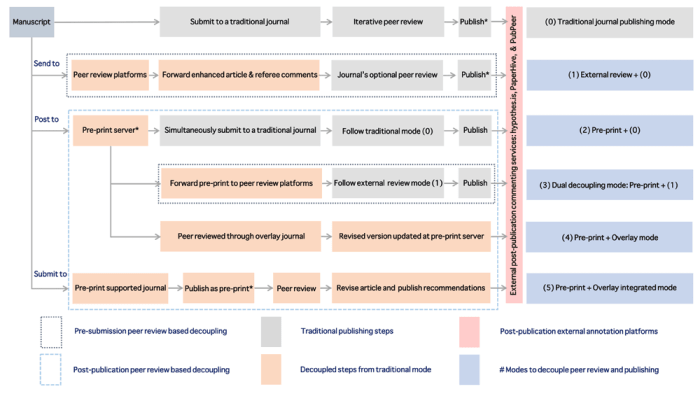

The dotted border lines in the figure highlight this element, with boxes colored in orange representing decoupled steps from the traditional publishing model (0) and the ones colored gray depicting the traditional publishing model itself. Pre-submission peer review based decoupling (1) offers a route to enhance a manuscript before submitting it to a traditional journal; post-publication peer review based decoupling follows preprint first mode through four different ways (2, 3, 4, and 5) for revision and acceptance. Dual-decoupling (3) is when a manuscript initially posted as a preprint (first decoupling) is sent for external peer review (second decoupling) before its formal submission to a traditional journal. The asterisks in the figure indicate when the manuscript first enters the public view irrespective of its peer review status.

While there is much potential value in anonymity, the corollary is also problematic in that anonymity can lead to reviewers being more aggressive, biased, negligent, orthodox, entitled, and politicized in their language and evaluation, as they have no fear of negative consequences for their actions other than from the editor. (Lee et al., 2013; Weicher, 2008). In theory, anonymous reviewers are protected from potential backlashes for expressing themselves fully and therefore are more likely to be more honest in their assessments. Some evidence suggests that single-blind peer review has a detrimental impact on new authors, and strengthens the harmful effects of ingroup-outgroup behaviours (Seeber & Bacchelli, 2017). Furthermore, by protecting the referees’ identities, journals lose an aspect of the prestige, quality, and validation in the review process, leaving researchers to guess or assume this important aspect post-publication. The transparency associated with signed peer review aims to avoid competition and conflicts of interest that can potentially arise for any number of financial and non-financial reasons, as well as due to the fact that referees are often the closest competitors to the authors, as they will naturally tend to be the most competent to assess the research (Campanario, 1998a; Campanario, 1998b). There is additional evidence to suggest that double blind review can increase the acceptance rate of women-authored articles in the published literature (Darling, 2015).

On the other hand, eponymous peer review has the potential to inject responsibility into the system by encouraging increased civility, accountability, declaration of biases and conflicts of interest, and more thoughtful reviews (Boldt, 2011; Cope & Kalantzis, 2009; Fitzpatrick, 2010; Janowicz & Hitzler, 2012; Lipworth et al., 2011; Mulligan et al., 2013). Identification also helps to extend the process to become more of an ongoing, community-driven dialogue rather than a singular, static event (Bornmann et al., 2012; Maharg & Duncan, 2007). However, there is scope for the peer review to become less critical, skewed, and biased by community selectivity. If the anonymity of the reviewers is removed while maintaining author anonymity at any time during peer review, a skew and extreme accountability is imposed upon the reviewers, while authors remain relatively protected from any potential prejudices against them. However, such transparency provides, in theory, a mode of validation and should mitigate corruption as any association between authors and reviewers would be exposed. Yet, this approach has a clear disadvantage, in that accountability becomes extremely one-sided. Another possible result of this is that reviewers could be stricter in their appraisals within an already conservative environment, and thereby further prevent the publication of research. As such, we can see that strong, but often conflicting arguments and attitudes exist for both sides of the anonymity debate (see e.g., Prechelt et al. (2017); Seeber & Bacchelli (2017)), and are deeply linked to critical discussions about power dynamics in peer review (Lipworth & Kerridge, 2011).

Reference

Tennant JP, Dugan JM, Graziotin D et al. A multi-disciplinary perspective on emergent and future innovations in peer review [version 3; referees: 2 approved]. F1000Research 2017, 6:1151 (doi: 10.12688/f1000research.12037.3)

2 thoughts on “11. Peer Review: Anonymity Versus Identification”